Mni Wičoni; Water is Life.

This Lakota expression was on the lips of attendees at the opening ceremony for an exhibition focused on the activism of Standing Rock water protectors at the Wyandotte’s Downriver Council for the Arts in this Detroit suburb.

Though the Standing Rock controversy was the focus of the exhibition, art from local Native Americans was featured as well, and issues affecting Native Americans in the Great Lakes were brought up.

Dr. Kay McGowan, an anthropology professor at Eastern Michigan University and volunteer with American Indian Services, has been using this traveling exhibit to highlight other industrial projects that have drawn criticism from Native American groups in the Great Lakes region.

“Our issues here are the same issues they have in other parts of the country,” she said. “It might be a different company, it might not be a Canadian company that wants to put in the pipeline, but it’s the same kind of destruction of the water, the environment that we’re seriously concerned with. All the tribal communities have come out against [Enbridge] Line 5 and Line 3,” she said.

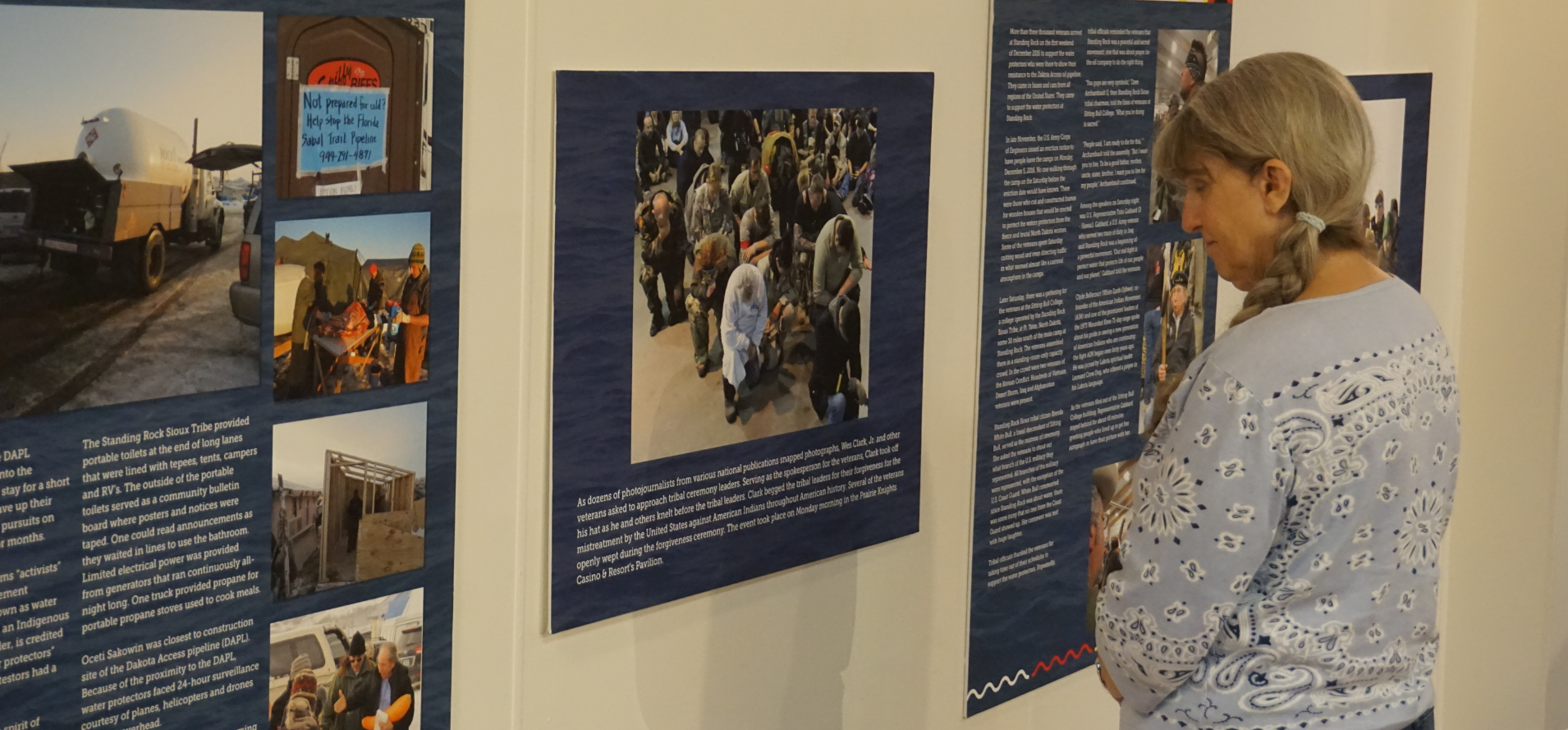

At the exhibit, walking straight from the entrance hall, visitors see an open space lined with displays of blown-up photographs taken by Levi Rickert.

Rickert, a member of the Prairie Band Potawatomi Nation and founder of Native News Online, took the photographs during his coverage of the Dakota Access Pipeline protests on or near the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in North and South Dakota.

Levi Rickert (left) chats with Warren Petoskey ahead of Rickert’s presentation

The exhibit runs through June 4, with free parking and admittance for visitors, and is split between the entrance level containing the Standing Rock photo exhibit and a lower level displaying artwork by and of local Native Americans.

Water quality and access to clean water was at the forefront of issues discussed by Rickert during his introductory presentation. Alongside basic environmental concerns, the art show also addresses issues of tribal sovereignty and treaty rights, the right to protest, and the continuing need for public services to assist Native American youth and senior citizens.

“This is something that deserves a lot of attention and exposure and I know for myself I’ll leave here thinking about this beyond our time here today,” said Jennifer de Beausset, an attendee and resident of Grosse Ile.

Looping back to a point he made at the beginning of his speech, where he insisted that folks in attendance remain politically engaged, Rickert emphasized how the issues of Standing Rock, while directly impacting the Sioux peoples, had consequences that would impact the rest of America as well.

“I think there’s about eight different projects across the country that Native American communities are protesting,” he said. “State lawmakers in some of the Great Plains states have now banned, if 10 people or more are protesting you become part of a ‘riot,’ they’ve written all this legislation that makes it really hard where people can go to jail for up to 10 years.

Artwork made by American Indian Services’ youth group

A section of wall downstairs is dedicated to photographs of pow-wows and of JoAnne Shenandoah, a Grammy-nominated folk singer and member of the Oneida Nation. The images were taken by Ralph Rinaldi, a retired educator who taught in the Detroit area..

“It’s no big secret that what I’m doing is keeping the culture alive and passing all that onto and showing it to the general public as well as to the Native American community,” Rinaldi said.

In one corner of the Standing Rock photo exhibit, a row of tables features artwork from American Indian Services and their youth program. Adjacent is a display of necklaces and beadwork made by elder members of the North American Indian Association of Detroit. At the far end, behind displays of his sister’s beaded Christmas ornaments and daughter’s hand-made earrings, sits Warren Petoskey.

“We were entitled to clean air, clean water and a clean Earth,” he said. “When you look at this continent, what was attractive about this continent was that it was unexploited, it was clean, you could drink from any stream or lake, and in 477 years look what’s happened.”