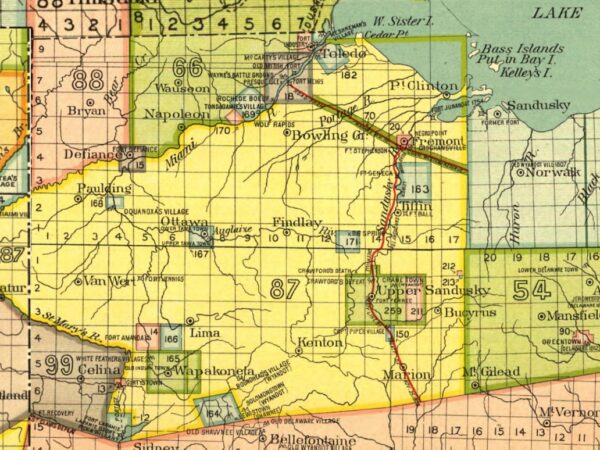

As Lake Erie’s annual algae bloom approaches, fingers are now pointing at animal farms as an increasing source of the nutrients washing into the lake.

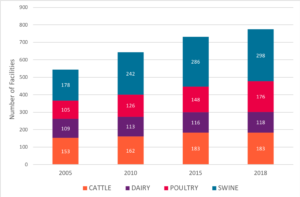

A year-long study says it’s likely animal farms in the Maumee River watershed are contributing more nutrients into Lake Erie each year and that, from 2005 to 2018, the number of unregulated farms increased by 40 percent.

The growing number of CAFOs by animal, Photo by Environmental Working Group and Environmental Law & Policy Center

The investigation indicates at least a quarter of the total farms in the watershed have expanded since their construction and at least half the manure generated in Ohio’s portion of the watershed comes from operations lacking state permits.

The work, conducted by The Environmental Working Group (EWG) in Washington D.C. and the Environmental Law & Policy Center (ELPC) in Chicago, is based on information retrieved through aerial photos, satellite imagery and state permit data collected from agriculture and environmental officials in Ohio, Michigan and Indiana. Scientists estimate the Maumee contributes about 30 percent of the phosphorous entering Lake Erie each year.

Animal farmers in the area, however, feel the study and the blame aren’t warranted.

“Preserving Ohio’s waterways is a daily job for farmers – it’s our responsibility and our obligation,” the Ohio Livestock Coalition said in a statement. “While we take very seriously credible scientific studies of nutrient runoff, the report from EWG fails to meet that test. Understanding nutrient management and water quality requires credible, on the ground, actionable research – not a collection of aerial photos.”

Animal farms negating efforts of crop farmers

There are currently 775 confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs) in the watershed, Sarah Porter, EWG senior analyst and policy manager, said. In 2005 there were just 545.

These operations concentrate large numbers of animals into a small area, producing massive amounts of animal waste. And that waste, researchers say, is negating the gains which tens of thousands of farmers growing corn, wheat, soybeans and other crops have made in reducing nutrient run-off from fertilizers applied to fields.

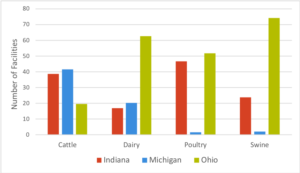

“We saw the highest amount of regulation in Indiana,” Porter said. “So officials there have more knowledge and more requirements on the manure management plans in that state.”

The growing number of CAFOs by state, Photo by Environmental Working Group and Environmental Law & Policy Center

The major issue, she said, is that unpermitted or unregulated animal farms are adding nutrients to the Maumee that aren’t being accounted for.

The study includes an interactive map illustrating the size and location of CAFOs and also the number operating in 2005 versus 2018.

In 2018 the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency reported phosphorous entering Lake Erie has remained steady in the last several years, despite the efforts of crop farmers. Widespread adoption of best management practices by farmers include the use of cover crops during winter, buffer strips along field edges, subsurface placement of fertilizers, and extensive soil testing in conjunction with computerized models to reduce the amount of fertilizer applied – especially important when portions of fields are shown to need little or no fertilizer.

Despite these efforts, the nutrients continue to flow from the Maumee into the lake – and study authors say CAFOs are replacing the nutrients crop farmers have eliminated.

Especially unregulated CAFOs.

Critics say study is deeply flawed – and deceptive

Kevin Elder is a farmer, and the retired chief of livestock permitting, a division of the Ohio Department of Natural Resources. He said the report is lacking balance.

“It really portrays one side without having actually been on a farm or seeing what they do,” he said, adding that such a study conducted almost solely from a desk and computer doesn’t have much merit. “The animal sector is always under the microscope, and this isn’t the first report EWG’s put out. I’ve never really seen a positive one.”

According to Elder, EWG and ELPC are playing fast and loose with the words “permit” and “regulate.” The two are different, he said.

“All farms are regulated, they’re just not all permitted,” he said. “There are extensive regulations under the Division of Soil and Water Conservation and under the Ohio Revised Code that specify what is required for farms that aren’t big enough to permit – they still can’t pollute, they still have manure application restrictions, there’s a whole bunch of regulations.”

The smaller operations which the report classifies as unregulated all follow legal rules and regulations regarding nutrients, their applications and control, Elder said. Just because a CAFO isn’t permitted doesn’t mean it’s polluting Ohio’s waters or not following strict regulations.

“There is no single contributor to elevated phosphorus levels, there is no rational reason to single out livestock farmers, and there will be no singular answer to address Ohio’s water quality challenges,” the statement from the Ohio Livestock Coalition said. “That is why Ohio’s farmers have invested millions in voluntary efforts to reduce nutrient runoff, have supported comprehensive regulatory reforms, and have contributed thousands of hours toward identifying workable solutions to protect Ohio’s lakes, rivers and streams.”

Ohio and Michigan follow federal standards

In Ohio and Michigan only CAFOs classified as “large” are regulated, according to the report. Rules governing these CAFOs cover things like construction of facilities, manure, wastewater and nutrients management. In these states, United States Environmental Protection Agency guidelines are used to determine whether an operation is a large CAFO or not. That federal threshold includes 1,000 or more cattle, 2,500 or more swine (10,000 under 55 pounds) and between 30,000 and 125,000 chickens (types and manure systems vary).

The regulation process in Ohio is overseen by the Ohio Department of Agriculture’s Division of Livestock Environmental Permitting, while the Ohio EPA oversees large CAFOs’ spills, runoff and some discharges.

“The Ohio Department of Agriculture’s priority has and will continue to operate a thorough and reasonable permitting program that protects water quality while allowing agriculture to remain productive,” said Brett Gates, deputy communications director for the ODA. Gates said Ohio farmers want to be a part of the solution when it comes to water quality in Ohio streams, rivers, ponds and Lake Erie, and they are currently working hard at it.

The problem, according to Porter, is the unregulated operations which fall below the large CAFO threshold.

“Without a permit,” she said, “you can still run a significant operation, without the development of a manure management plan where you actually identify how much manure you’ll be creating or ensuring you have enough storage or where you’ll be applying the manure.”

Indiana rules stricter than Ohio and Michigan

Indiana doesn’t rely on the federal numbers in determining if a farm needs permitting. Officials there set their own rules, regulating operations with 300 or more cattle, 600 or more swine and 30,000 or more poultry – far below the thresholds Michigan and Ohio use.

According to Barry Sneed, public information officer with the Indiana Department of Environmental Management, CAFOs operate under the very careful eye of regulators. That includes pre-construction, construction and operation.

“Indiana has regulated farms since the 1970s, and presently regulates over 1,830 farms under the state’s permit process,” he explained. “If the state were to only regulate what the US EPA requires, zero farms in Indiana would be regulated.”

Regulated CAFOs operating in Indiana are required to be zero discharge, Sneed said.

Maumee River watershed largest in Great Lakes

The 137-mile-long river drains 8,000-plus square miles of land which is about 66-percent agricultural.

The problem with the Maumee watershed, according to Porter, is the number of CAFOs that fall below the US EPA’s regulation threshold. And that’s most of them, she said.

“Out of the 775 operations, about 140 to 145 are permitted, so that’s about 20 percent of the operations permitted,” she said. The rest, according to Porter, are operating below the radar without the scrutiny the large CAFOs receive.

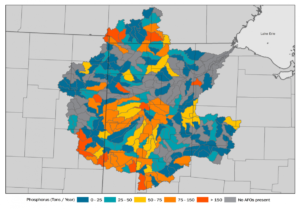

Areas where phosphorous production is concentrated, Photo by Environmental Working Group and Environmental Law & Policy Center

“I don’t think there are any large operations out there that should have a permit that don’t, just that when you add the unpermitted operations to the permitted, you don’t have an estimate on how many total animals there are. And they tend to be clustered, so there’s a lot of manure being generated in one place,” Porter explained.

Porter said, for necessary economic reasons, CAFOs tend to be clustered in areas near slaughterhouses. That concentrates a lot of manure in one area, limiting how much can be reasonably utilized on nearby fields.

“The farther you go the more costly it is to truck away from sites. There’s been a lot of research on that, and about 75 percent of the manure is applied within three miles of an operation, she said.

How much manure is there? The short answer is, a lot. Between dairy and beef cattle, swine and poultry there are an estimated 20.4 million animals in the Maumee watershed producing millions of tons of manure each year.

In 2005, animals in the watershed produced about 3.87 million tons of manure annually. By 2018 the amount produced by CAFO’s had increased to 5.53 million tons.

Phosphorous from hog, poultry manure doubled since 2005

In 2005 poultry manure produced phosphorous in the watershed estimated at about 1,600 tons, and has risen to just under 4,000 tons in 2018. Hog manure phosphorous rose during the same period from just under 2,000 tons to about 3,600 tons annually.

Cattle and dairy operations’ output remained steady, rising only slightly during the same period. The total phosphorous produced in the Maumee watershed is currently estimated to be about 10,600 tons annually.

Madeline Fleisher, Senior attorney at the Environmental and Policy Law Center,Photo by Environmental Working Group and Environmental Law & Policy Center

“What we’re focused on is what everyone knows is a problem, phosphorous pollution in Lake Erie,” said Madeline Fleisher, senior attorney for ELPC. “And if you look where it’s coming from no one will dispute that about 90 percent is coming from agricultural sources.”

Fleisher said the study isn’t looking at what are considered family farms, where people have a half dozen cattle, a small flock of chickens. “These are big operations, especially in Ohio, which were sort of captured in this report,” she said. “The bottom line is they produce a lot of manure which is getting into the watershed and is not subject to permitting requirements.”

In addition to a growing manure problem, Fleisher said, there’s also a regulation disparity between animal waste and commercial fertilizer, in application rules. “Under existing state law in Ohio and regionally, manure is generally subject to looser rules, in terms of how much you can put on fields and the oversight and attention it gets,” she explained. “If you’re a row crop farmer you’re probably trying to manage it because you don’t want to purchase more than you need to, but if you’re a big animal operation, you’re producing manure as waste and you’ve got to get rid of it.”

One story, two sides

Fleisher said when it comes to CAFOs whose animal numbers fall below large CAFO classifications standards, no one is minding the store.

“In terms of really how much gets placed on the ground and is being washed into Lake Erie, putting that information together with the growth trend of these larger animal operations is something people should really be keeping an eye on,” she said.

Elder agrees, and said the agriculture industry welcomes inquiry and visits.

“I would encourage people who are interested and concerned to actually go to farms and talk to farmers,” he said. “The pork producers, the cattlemen, the poultry folks, they would all put people who have concerns in contact with producers who are doing what is recommended.”

Featured Image: Lake Erie algae blooms, Photo by Environmental Working Group and Environmental Law & Policy Center.