Canadian researchers are studying how to help prevent the spread of this fish

It was the fish’s failures as an invasive species, perhaps more than its successes, that first drew Sunči Avlijaš to studying tench.

The PhD candidate in conservation biology at Montreal’s McGill University first began studying the Great Lakes’ latest invasive fish in 2014 under the supervision of well-known invasion biologist Anthony Ricciardi. And while tench were a common invasive in other parts of the world, few in the Great Lakes had heard about them despite their presence in the basin since the 1980s.

“Tench has had this really varied success in invading the areas where it was introduced,” Avlijaš said. “Nobody really thought that tench was going to be increasing its population and spreading quite like it has over the past few years.”

Alongside Ricciardi, she began studying U.S. Geological Survey maps of where tench exist throughout the United States and Canada. “Of all the places where it was introduced, there were many, many areas where it didn’t succeed,” she said. “It just seems like when it takes off, it does become really dense, and we were interested in using this big variation in success to study the characteristics of the sites where they were introduced.”

Map provided by Iman Saleh, GLN/DPTV

Knowing what habitat, water quality and food conditions the tench respond well to could help resource officials know where tench were likely to thrive and, ultimately, where they should direct any effort to remove them from waterways.

But what, exactly, are tench?

Tinca tinca

Tinca tinca, also known as tench, are native in Europe and Asia from France on the Atlantic Ocean to China’s interior. Humans, meanwhile, have introduced them to every continent but Antarctica.

While most tench grow to 10 inches long, some that Avlijaš and her team have captured in the St. Lawrence River system have measured more than 28 inches.

“They are large fish,” she said, and consume huge quantities of snails and insect larvae, food sources that numerous native species also depend on. The result is added pressure on natives, some of which are already struggling from habitat loss and pollution.

One such species-at-risk is the River Redhorse, a native fish that has “suffered substantial declines” in the St. Lawrence and connected rivers, according to Environment Canada. The Redhorse is a rarity among freshwater fish in that it survives almost entirely by eating molluscs, a favorite food of tench. Any added pressures these invasive fish place on the already heavily-weighted Redhorse could push them to local extinction.

Yellow perch, an important commercial and recreational fish throughout the Great Lakes, is also thought to be suffering under increased competition with tench for food.

Tench Arrive in the Great Lakes

Tench in Canada largely trace their origin back to a single Quebec farmer operating near the Richelieu River in Quebec. Despite being denied permits from the Quebec government in the 1980s to import tench from Germany to raise as food fish, the farmer hopped a commercial flight to Europe and returned with about 30 tench in a picnic cooler. The researchers say they have documents showing when they were brought into the country.

Back in Quebec, the farmer stocked tench in several ponds on his property near St. Alexandre before discovering the fish had no market in North America. It still doesn’t.

By 1991, the farmer had drained his ponds, allowing the fish to swim through agricultural runoff and into the Richelieu River. Just three years later, tench were turning up in the catches of commercial fishers in the St. Lawrence Seaway.

The species has been living in other parts of North America for a century and a half. According to the U.S. Geological Survey, tench were first reported in Maryland waterways as far back as 1874. Their populations exploded after the U.S. Fish Commission introduced them from Germany three years later as a potential food source and sport fish.

These days, heavy concentrations of the fish can be found everywhere from San Francisco and Washington State to the Rio Grande River in Colorado, and from Chesapeake Bay north to Montreal along Lake Champlain and the Richelieu River.

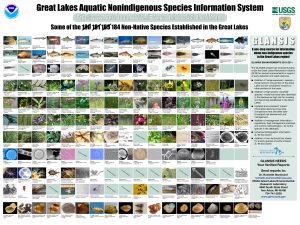

But until recently, tench have been largely kept out of the Great Lakes Basin, a watershed that already contains almost 190 non-native species, many of which have moved seamlessly into the Mississippi River system through the porous Chicago River.

In part, that’s what makes the October 2018 discovery of tench in the Bay of Quinte near Belleville, Ontario, so worrying.

“That’s the first capture on Lake Ontario to date,” Avlijaš said. Before 2016, researchers didn’t think the fish were able to move far upstream along the St. Lawrence River. Massive hydroelectric dams, built by power generators in Ontario and New York State in the late 1950s, stood in their way.

Yet tench soon began showing up in Lake St. Francis in the St. Lawrence Seaway, running up against turbines from the 1,045-megawatt Moses-Saunders dam straddling Ontario and New York. The following year, anglers caught tench near Cornwall, Ontario. What were once one-off catches were become alarmingly regular finds.

And the research that Avlijaš and Anthony Ricciardi began at McGill has, to date, shown largely that tench can survive equally well in shallow, plant-heavy wetland areas as they can in deep and rocky waterways devoid of plant life. Habitat conditions that were once hoped to be barriers to tench feeding and spawning have proven to have little to no impact on their ability to thrive.

Avlijaš stresses that anglers aren’t catching many of the invasive fish at a time; but the steady push further upstream into Lake Ontario is disturbing. “They seem to be spreading really rapidly for a fish that has mostly hung out in the Richelieu River for a couple of decades,” she said.

The north shore of Lake Ontario isn’t the only location where tench have turned up unexpectedly. In 2014, Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources staff were alerted to a pond near Orangeville at the headwaters of the Humber River that was illegally stocked with tench. While MNR staff destroyed whatever illegal fish they found on the farm north-west of Toronto, Avlijaš and her colleagues wrote in a 2017 paper on tench in the Great Lakes that “it is highly likely that unreported tench inhabit other ponds” near Orangeville.

Public Outreach One Key to Halting Tench

All of which makes the importance of greater public awareness and recognition so crucial to halting their spread. Anglers often mistake tench for other baitfish, and the species itself is capable of living in even the dirtiest of bait buckets and live wells.

So while governments and agencies in Canada and the United States need to boost enforcement of existing barriers to illegal fish transport, they must also step up their public outreach efforts to let everyone – especially recreational and commercial anglers – know the dangers tench pose to the basin’s ecological stability.

Because if people continue moving tench upstream and stocking them in illegal ponds, Avlijaš says, “it’s a waste of money to do anything else.”

Featured Image: Sunči-Avlijaš, PhD candidate in conservation biology at McGill University, Photo by Sandra Svoboda

Editor’s Note: Reporting for this article was made possible by the Institute for Journalism and Natural Resources.

2 Comments

-

If there are mussel eaters, would they not be valuable in controlling Zebra/ Quagga mussles in all the great lakes and infestation in smaller lakes and ponds in and around all the Great Lakes?

-

Your question about using an invasive species to control other invasive species reminds me of the childhood song “I know an old lady who swallowed a fly . . . ”

The unintended consequences are the problem.

I’d like to, Terminator-style, go back in time and stop every as*hat in history who has brought species of animals and plants around the globe for their own profit, with no care about any future destruction they’d be wreaking.

-