Premier Doug Ford has vowed to make Ontario “open-for-business,” but recent backlash from municipalities, farmers and environmentalists has forced a re-think

After introducing developer-friendly legislation in December that critics claimed would rollback source drinking water protections and key aspects of the Great Lakes Protection Act, the Ontario government announced last week it would eliminate the most contentious portion of the bill.

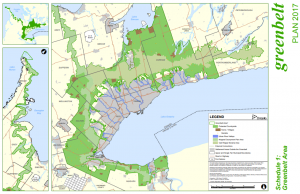

Steve Clark, Ontario’s Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing, made the surprise announcement on Twitter Wednesday afternoon. While the government had no intention of using Bill 66 to shrink the Greenbelt, he said, a 2,800-square-mile greenspace surrounding the City of Toronto, the government had “listened to the concerns raised by [Members of Provincial Parliament], municipalities and stakeholders” and would strike out Schedule 10 from the bill.

Restoring Ontario’s Competitiveness Act, also known as Bill 66, was introduced Dec. 6. While few aspects of the legislation were palatable to many environment NGOs and local governments, Schedule 10 proved an especially bitter pill to swallow for the fear it raised about how much Premier Ford’s ‘Open for Business’ mantra would run roughshod over environmental regulation.

At the heart of Schedule 10 was a proposed change to provincial planning policy allowing local governments to pass so-called “open-for-business” zoning by-laws. These by-laws would allow local councils to skirt regulations currently in place to protect drinking water supplies set out in powerful pieces of legislation like the Clean Water Act. Weakening the Clean Water Act was previously considered political suicide given the preventable tragedy leading to its creation.

In 2000 in the small town of Walkerton, Ontario, environmental factors, coupled with years of deregulation from a cost-cutting conservative government not unlike Ford’s, led to a water-based E. coli outbreak in the town of 5,000. More than 2,300 people fell ill, including young children; seven died.

“That Act led to all these source-water protection plans and contributed to being able to provide the people of Ontario with safe drinking water,” says Nandita Basu, an engineer with the University of Waterloo’s water sustainability and ecohydrology department.

One of the key reasons why Walkerton’s water contamination happened at all was the long-held practice of spreading manure on snowy agricultural land, Basu says. An extreme weather event in 2000 washed huge quantities of the manure into local waterways which, ultimately, led to the contamination.

“I think [these regulations are] even more important today,” she says, “because the climate is changing. We’re having more of these extreme rainfall events, and we should be even more cognizant now than before that those regulations that protect our drinking water need to be protected.”

After Walkerton, and the passage of the Clean Water Act in 2006, concerns remained about the quality of water drawn from private wells. But at a minimum, the legislation ensured the drinking water of 80 percent of Ontarians hooked up to municipal sources would be safe. Bill 66 took away even that vital protection, Basu says. “It’s not a very prudent way of moving forward. It’s moving backward.”

Theresa McClenaghan agrees. Creating new employment opportunities is one thing, says the head of the Canadian Environmental Law Association. But the Ontario government has been so singular in their job-creating drive that, beyond platitudes, Ford and his ministers have offered no effective counterpoint acknowledging the importance of clean water to people living in the Great Lakes basin and beyond.

Theresa McClenaghan, Executive Director and Counsel, Canadian Environmental Law Association, Photo by cela.ca cc 4.0

Regulations protecting water quality have been categorized by government ministers as nothing more than “red tape,” McClenaghan tells Great Lakes Now. “And that ‘red tape’ automatically means ‘bad’. This is not the case, as [the Clean Water Act provides] very, very important public protection provisions.”

After Walkerton, the government was dutiful in consulting with a wide variety of stakeholders to put legislation in place that would keep widespread water contamination from happening again. Yet Bill 66 gives tremendous power to local councils and the Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing to skirt those protections, McClenaghan says, well away from the public eye.

Since the bill was unveiled, environmental organizations found common cause with powerhouse farmers’ groups like the Ontario Federation of Agriculture and big city governments to halt as many contentious aspects of Bill 66 as possible.

Guelph mayor Cam Guthrie told reporters he would “never want to agree to anything” that threatened the city’s water supply. The mayors of Hamilton and Burlington, two cities straddling the north shore of Lake Ontario west of Toronto, said immediately after the bill’s release they’re not interested in creating more development land that could threaten local waterways, so much as encourage smarter development on existing industrial land.

Ontario Nature helped organize a rally outside Environment, Conservation and Parks Minister Rod Phillips constituency office in Ajax in protest; OFA president Keith Currie, meanwhile, wrote to Economic Development Minister Todd Smith calling the bill a “direct attack” on family farms in Ontario.

Given the premier’s habit of railing against “downtown elites” when the mood strikes him, the government was perhaps willing to write-off the opposition of environmental groups and big city mayors. But for a government largely made up of rural and suburban ridings, and just seven months into a four year mandate, it appears that upsetting the province’s largest agricultural lobby group was a step too far.

Caroline Schultz, executive director of Ontario Nature, said in a statement she was “thrilled” to see the government step back from “one of the most alarming attacks on the environment we have seen in decades” in Schedule 10.

“This is a major victory for the citizens who put up lawn signs, signed petitions, made calls to their MPPs and rallied outside of their offices,” said Environmental Defense head Tim Grey. “It also speaks to the power of the farmers, businesses and many Municipal leaders who publicly opposed the Bill, and instead put farmland, natural areas and drinking water first.”

Bill 66 is expected to be called for further debate in February.

Featured Image: Steve Clark, Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing, announcing the construction of a new Mimico GO Station, Photo by Government of Ontario