Entrenched legislatures and high expectations present challenges

Election campaigns for political office seem never-ending when they span many months. But once the winners are in office, the honeymoon is usually brief.

Election night rally, Photo by Tony via wikimedia cc 2.0

Constituents have big expectations for their newly-minted officials, and the winners have to come to grips with the fact that governing isn’t campaigning.

That’s the reality for two gubernatorial election winners in key Great Lakes states. Both are Democrats who will replace two-term Republicans.

Gretchen Whitmer in Michigan and Tony Evers in Wisconsin are the incoming Democrats, and they face significant issues related to water.

It’s especially true for them since both made clean water a campaign issue and both inherit an entrenched Republican legislature, which means they don’t have a clear path to implementation of their agendas.

What should be their priorities? What are the chances of success and what are the barriers to delivering on campaign promises?

Great Lakes Now asked activists and observers in each state to weigh in.

Gretchen Whitmer needs to lead in Michigan

The Whitmer campaign had an ambitious list of water priorities, and longtime environmental advocate Cyndi Roper acknowledged that it’s an aggressive agenda. But Roper said “Whitmer wants to deliver on it.”

Roper is a Senior Policy Advocate for the Natural Resources Defense Council in Michigan.

With PFAS threatening water supplies around the state, Roper said Whitmer’s Department of Environmental Quality could set a drinking water standard by creating a rule that would expedite the process.

As lead in drinking water is still an omnipresent issue, Roper said Whitmer should give a high priority to implementing outgoing Gov. Rick Snyder’s Lead and Copper Rule. The rule was developed by the Snyder administration in the wake of the Flint water crisis and absent an updated federal standard. The administration says the rule is a model for other states to follow.

Cyndi Roper, Natural Resources Defense Council, Photo provided by Gary Wilson

“Whitmer needs to take a leadership role to secure funding for water infrastructure,” Roper said, and she expects that will happen. Pre-election polling in Michigan showed improving water infrastructure is a top priority.

When you’re the governor of Michigan, other Great Lakes states often look to you to be a de facto leader on regional environmental issues. That has been the case for the last eight years on Asian carp and water diversions. Whitmer will have to decide if she wants to accept that role or stay strictly within organizational parameters.

Roper had advice for Whitmer supporters who have high expectations and who will expect her to rapidly enact her water agenda.

“No one person, not even the state’s chief executive, can solve the state’s problems,”

Roper said she urges citizens to “stay engaged and focused and be part of the process” for the long term.

Moving public opinion in Wisconsin

Political observer James Rowen in Wisconsin noted the short honeymoon voters provide and said, “As governor, Tony Evers needs to move quickly on the basic environmental and public health matters which outgoing Gov. Scott Walker had disregarded.”

Rowen writes The Political Environment blog.

Rowen told Great Lakes Now, “Evers will probably have to try and move public opinion in his favor if the Republican legislature gets in the way.”

He expects Evers to appoint executives who will “recast” the Department of Natural Resources’ mission toward conservation and the public interest, and away from the “chamber of commerce mentality” preferred by Walker. That mindset prioritized economic development over conservation according to Walker’s critics.

James Rowen, political writer, courtesy of jsonline.com

Rowen listed preserving wetlands, working with the new attorney general to re-energize respect for the Public Trust Doctrine, incorporating downstream impacts in high-capacity well withdrawal permitting and better monitoring and enforcement of discharges to groundwater from large animal feeding facilities (CAFOs) as priorities.

Wisconsin was recently featured in a New York Times article on groundwater pollution from industrial agriculture production.

Evers inherits the Foxconn deal that provides subsidies and relaxed environmental rules to the tech-giant in exchange for setting up a manufacturing operation in Southeast Wisconsin. It also includes a controversial diversion of Lake Michigan water to support the operation. The diversion still faces a legal challenge brought by environmental groups.

Rowen said while Evers has been critical of the financial subsidies and environmental permit concessions provided to Foxconn, “it’s too soon to tell exactly what moves he has in mind.”

National water consultant and former Wisconsin environmental advocate Lynn Broaddus echoed Rowen’s sentiments about re-prioritizing the DNR’s mission.

Lynn Broaddus, President of Broadview Collaborative, Inc. , Photo by broadviewcollaborative.com

“We’re likely to see staff being able to talk about climate change again and get back to work helping communities prepare for increased rainfall and acceleration of a transition to clean power,” Broaddus told Great Lakes Now.

The Upper Midwest including Wisconsin and Michigan’s Upper Peninsula have experienced three, hundred-year type storms that have caused flooding and loss of life since 2012.

While Whitmer and Evers share similar challenges, Whitmer has one advantage that Evers doesn’t. She breezed to victory by a 10 percentage-point margin which gives her leverage when negotiating with recalcitrant legislators.

Evers has no such luxury as he eeked out a win by a razor-thin margin that wasn’t decided until the early hours of the morning.

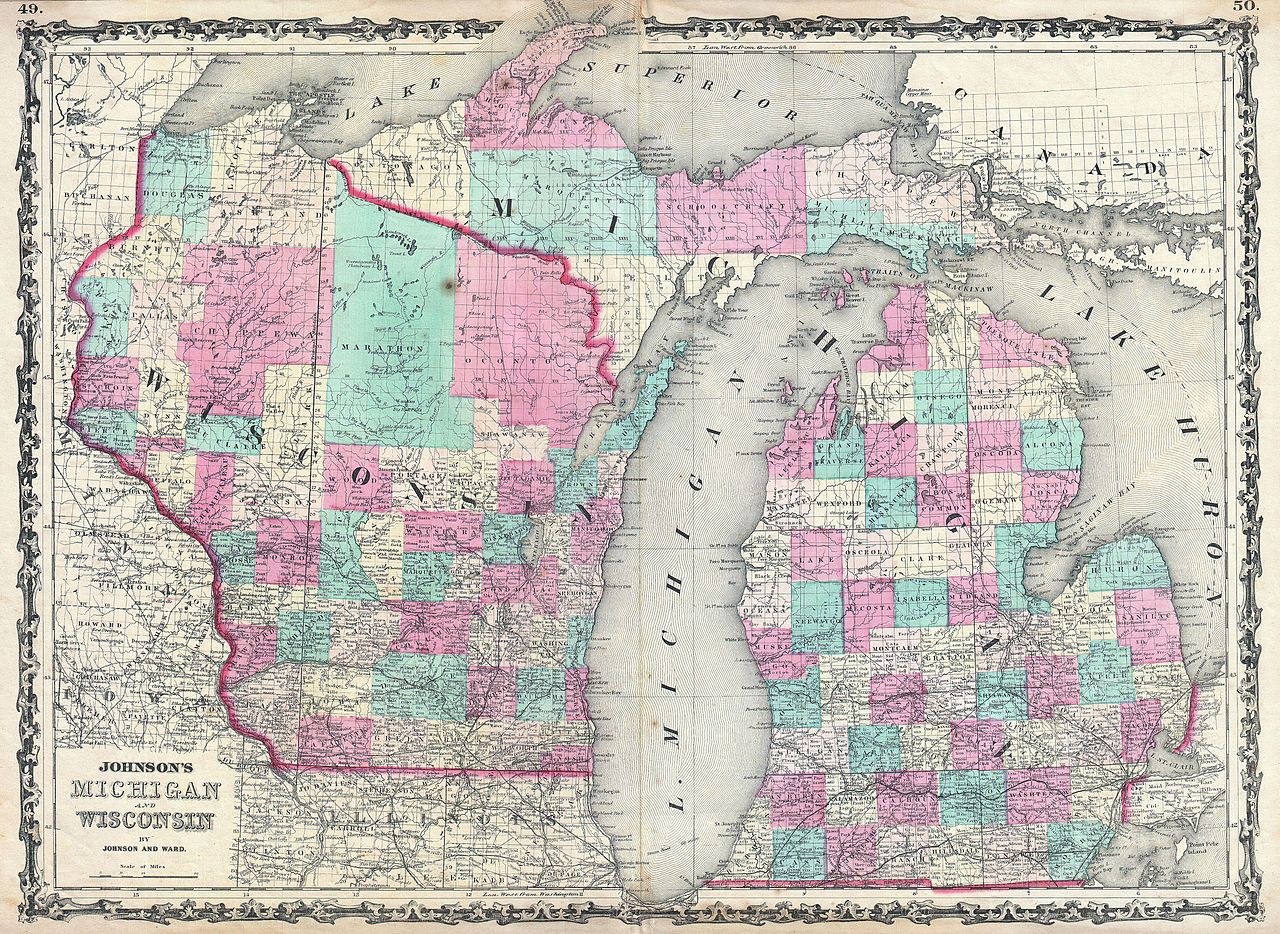

Featured Image: A. J. Johnson’s 1862 map of Michigan and Wisconsin, Illustrated by Alvin Jewett Johnson via wikimedia