Great Lakes Environmental group seeks court order to shut it down

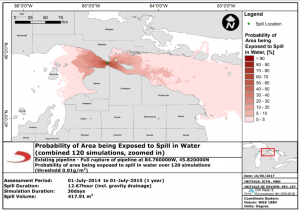

The newly released report, titled “Independent Risk Analysis for the Straits Pipelines,” details nine different worst case scenarios of what would happen if there was an oil spill in the 4.5 mile section of Enbridge’s Line 5 pipeline beneath the Straits of Mackinac.

The state-commissioned, independent analysis of the 65-year old pipeline which runs from Superior, Wisconsin to Sarnia, Ontario, evaluated Enbridge’s liability for a worst-case-scenario spill, including the impact on Michigan’s economy and environment.

Line 5 pipeline, Photo by dptv

The 645 mile-long pipeline carries 23 million gallons of oil and natural gas liquids across the Straits of Mackinac every day.

According to the analysis of more than 4,300 spill simulations, a rupture to both Straits pipelines – with concurrent failures of primary valves on each pipeline and secondary safety valves – could release up to 58,000 barrels of crude oil into the Great Lakes and impact more than 400 miles of shoreline in Michigan, Wisconsin and Canada based on wind and current conditions.

The report, headed up by a team at Michigan Technological University (MTU) says depending on the timing and magnitude of a spill, 47 wildlife species of concern and 60,000 acres of unique habitat could be at risk.

Worst-case Scenario Clean-up Costs: 2 Billion Dollars

The 396-page draft report calculates clean-up, restoration and liability costs from the worst-case scenario at almost $2 billion.

The report notes that “because cultural resources cannot be restored to baseline, their loss must be compensated through compensatory restoration.”

Most Great Lakes environmental groups say the results are frightening, and provide enough fuel to shut down the pipeline as soon as possible.

Enbridge spokesperson Ryan Duffy, Photo by Great Lakes Bureau

Enbridge disagrees. Spokesperson Ryan Duffy tells Great Lakes Now, “The scenarios presented in this report are purely hypothetical and the probability of the events actually occurring is extraordinarily unlikely because Enbridge operates our pipelines with multiple layers of safety in mind.” Duffy says, “These layers include a 24-hour control center that constantly monitors all of our lines and can initiate a shutdown in minutes; automatic shut-off valves located on either side of the Straits that would minimize the amount of product that could be released; and well-trained local personnel with emergency response equipment who could be onsite quickly.”

The National Wildlife Federation’s Communications Coordinator Drew Youngedyke’s response to the Enbridge statement? “Unfortunately, what Enbridge calls ‘low probability’ keeps happening. The anchor strike was a low probability six months before it happened, and I’m sure they considered the Kalamazoo River oil spill a low probability before it happened, too.”

The environmental group called FLOW (For Love of Water) in Traverse City goes even further.

It’s calling on Governor Snyder to seek a court order to shut down the 65-year-old Line 5 pipeline owned by Enbridge, which is based in Calgary, Alberta.

“The State of Michigan has a legal duty to protect the Great Lakes”

FLOW’s President and Founder, environmental attorney Jim Olson, tells Great Lakes Now his group has been trying to get Michigan’s Governor to take legal action against Enbridge for several years but he says Michigan’s Attorney General refuses to take North America’s largest energy infrastructure company to court. Olson says this report makes it clear: the risk is too great for Michigan and the freshwater source that surrounds the state.

Jim Olson, Founder & President, Photo by flowforwater.org

Olson says, “The State of Michigan has a legal duty to protect the Great Lakes as a public trust – a priceless treasure for the public to use and enjoy, not as a private waterway for a Canadian pipeline company with a terrible track record in Michigan.”

Mike Shriberg, Great Lakes Regional Executive Director for the National Wildlife Federation and a member of the Michigan Pipeline Safety Advisory Board, issued this statement after the release of the new risk assessment report: “One assumption that jumps out is that Enbridge would detect a leak within 5 minutes or less, when it took them 17 hours to detect the Kalamazoo River oil spill and weeks to assess the damage caused by this past April’s anchor strike. Given Enbridge’s track record, a 5-minute detection time seems closer to a best-case scenario, not a worst-case. Even with this estimate, the report outlines significant risks to northern Michigan communities, economy, tourism, recreation, fish and wildlife, and irreplaceable tribal and cultural resources which are far greater than the sliver of benefit anyone in Michigan receives from Line 5.”

“The Governor is continuing work on a decommissioning strategy for Line 5”

Great Lakes Now contacted Governor Snyder’s office to find out his response to this newly released risk assessment of the Line 5 pipeline. Deputy Press Secretary Tanya Baker tells Great Lakes Now: “The risk analysis report is preliminary and we expect to receive the final report from the MTU team after the public comment period. In the meantime, the Governor is continuing work on a decommissioning strategy for Line 5 with state departments.” Great Lakes Now asked for clarification of the term “decommissioning strategy.” Baker said, “Governor Snyder had said that, following studies that showed a tunnel is physically possible and construction wouldn’t cause significant environmental damage, he would move to require Enbridge to build a utility corridor and decommission the existing Line 5.”

This new risk assessment report comes a year later than previously scheduled by the Michigan Pipeline Safety Advisory Board, because the original report which was being conducted by the Norwegian company Det Norske Veritas was thrown out due to conflict of interest. An employee working on the Det Norske Veritas risk analysis had worked on another project for Enbridge – a violation of contract terms – but that fact did not come to light until just a few weeks before the original report was to be released last summer. Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette terminated the state’s contract with the firm saying it was the “only option we have to maintain the integrity of the risk analysis.”

Michigan Technology University’s Guy Meadows, who was selected to lead the team of 41 researchers for this new risk assessment report, conducted a total of 4,380 oil dispersal simulations over a one year period. (He recused himself and resigned from the Michigan Pipeline Safety Advisory Board after being selected to conduct the report.) He used meteorological, water current and ice cover conditions that he says are representative of seasonal conditions in the Straits. Meadows says the research took in to account previous hydrodynamic modeling capabilities to include wind transport of oil, ice-cover conditions and potential effects on oil dispersal and evaporation.

Meadows says, “I am proud of the way in which our universities have come together to provide a fact-based analysis of a very complex problem, under an extremely tight time frame. In conducting this work, we have also advanced knowledge about the fate and transport of oil in freshwater.”

Meadows is the Robbins Professor of Sustainable Marine Engineering and director of the Great Lakes Research Center at Michigan Tech. The Agency for Energy, the Attorney General’s Office the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) and Department of Natural Resources contracted with Michigan Tech for the risk analysis report.

The risk analysis team included 21 researchers from Michigan Tech and 20 from external organizations. Nine universities contributed to the analysis, seven of which are within the state of Michigan: Michigan Tech, the University of Michigan, Michigan State University, Wayne State University, Western Michigan University, Grand Valley State University and Oakland University. The two out-of-state universities are North Dakota State University and Loyola University Chicago.

“The largest foreseeable discharge of oil”

The researchers identified the magnitude of a “worst case” oil spill, analyzed the likely environmental fate and transport of oil or other products released from the Straits Pipelines in a worst-case scenario, analyzed how long it would take to contain and clean up the spill and the public health, safety and ecological impacts, among many other measures. The team also analyzed potential measures to restore affected natural resources as well as governmental costs in the event of a worst-case release.

Members of the team also assessed what the report calls broader impacts of a worst-case scenario spill to assess the perceived risks and concerns expressed by local communities, civil society groups, indigenous communities, governmental agencies and the public at large,

Because no oil spill as large as the scenarios analyzed in the report has ever occurred in the waters of the Great Lakes, researchers reviewed a selection of other similar events in order to evaluate the potential impacts of a Straits spill. They based their approach on an accumulation of worst-case assumptions that were consistent with the federal definition of “the largest foreseeable discharge of oil,” to determine the maximum possible volume that could be released.

By definition, the worst-case spill size is much larger than would be expected under average or typical conditions. According to the draft report, the impacts of a spill depend on when it occurs and how meteorological conditions disperse the oil.

The report says the definition of a worst-case scenario also varies, depending on which impacts are being assessed. For example, the report acknowledges a winter spill would be the most difficult to respond to safely and effectively, while a spill that occurred in the spring would generate the highest economic costs.

The spring scenario was used as the representative scenario to estimate the overall liability from a worst-case scenario spill at the Straits because a spill at that time of year, just prior to the summer tourism season in the Straits, would have the largest impact overall.

The report also considers various modes of failure for the Straits Pipelines and separates these failures into five tiers.

The public will have 30 days to comment on the report.

The risk analysis team will hold a public presentation on the draft report at 6pm on August 13, 2018, at the Boyne Highlands Convention Center in Harbor Springs, Michigan. When the public comment period closes, the team will prepare a final report to be delivered by September 15, 2018.

(The full press release of the new risk assessment report from the State of Michigan can be found here: ![]() )

)

For more on Line 5, watch greatlakesnow.org’s documentary “Beneath the Surface: The Line 5 Pipeline in the Great Lakes” on July 26th on Detroit Public Television at 9pm or watch it online at ![]()

Featured Image: Greetings from Mackinac Island postcard, Image by Found Image Holdings Inc

1 Comment

-

This is just another inaccurate Michigan media report which completely mis-states the applicable law and capabilities of Michigan govenment as to its powers and authority for shutting down an interstate hazardous liquid pipeline like Enbridge’s Line 5.

The controlling law which this Great Lakes Now report completely ignores is 49 USC Sec. 60104(c) which preempts all state regulation and standards of operation, design, maintenance, inspection, etc. for interstate hazardous liquid pipelines….an express federal preemption that controls over any state law requirements. Moreover, the report fails to note that Michigan does not have an statutory authority over such interstate hazardous liquid pipelines and that Michigan is NOT an agreement state to enforce federal requirements of the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration.

How does such a federal preemption work out in practice?

The City of Seattle found out in Seattle v. Olympic Pipeline Company in which 49 USC Sec. 60104(c) was the controlling law cited by Federal District Court and the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals when these courts found that the City was without any authority to enforce an easement agreement with the pipeline company:

https://caselaw.findlaw.com/us-9th-circuit/1058087.htmlAttorney Jim Olson will not address this federal preemption and its effect. If the Michigan Attorney General and/or Governor filed state litigation in state court to shut down Line 5, Enbridge would file a motion in Federal District Court for the Western District of Michigan to remove the case to federal jurisdiction where any such litigation would be rapidly dismissed.

If MIchigan AG Bill Schuette is behind and desperate enough in his race for governor in late October, he would probably carry out such stunt litigation using taxpayer dollars to try to get elected governor knowing that the voters would not find out it was all sham litigation until after the election by the time it was removed to federal court. In doing so, Schuette would eat Gretchen Whitmer’s political lunch since she has also engaged in the fairy tale that Michigan has shutdown authority over such interstate pipelines.