“Public engagement” sessions dot the region

The 14 year-old federal program to restore the Great Lakes to a semblance of environmental health after decades of degradation and neglect is in the public spotlight this summer.

It’s the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative, or GLRI, as it’s commonly referred to by agency staff, elected officials and advocates.

The initiative is approaching its third iteration, and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency is conducting what it’s calling “public engagement sessions” for input on priorities for the period 2020 to through 2024.

The process began in Toledo, Ohio last week and will continue throughout the summer at sites in the region.

Roots in the Bush era

GLRI’s roots go back to 2004 when President George W. Bush signed an executive order “directing his cabinet to establish the Great Lakes Interagency Task Force and promote a “Regional Collaboration of National Significance” for the Great Lakes.”

President George W. Bush signs the executive order establishing his Great Lakes Interagency Task Force, Photo by Paul Morse via whitehouse.archives.gov

Out of that order came a structure for restoring the Great Lakes that spans 16 federal agencies and still exists today in its original form.

President Obama put $475 million in his first budget for GLRI and it has been funded at $300 million annually since. To date, it has survived efforts by President Trump to eliminate the program and turn responsibility for it back to the states.

The U.S. EPA is the lead agency and since 2010 GLRI has worked on 4,000 projects expending $2.1 billion, according to the EPA’s restoration website.

Success

It’s primary focus area is cleaning up 31 toxic legacy sites that remain from their official designation in 1987 as Areas of Concern. The sites have received $800 million and the EPA recently told Great Lakes Now that “incredible progress” has been made since 2010 when money started flowing for the work after over 20 years of inertia.

In addition to cleaning up toxic sites, there’s been long-overdue progress on tracking and protecting coastal wetlands. The EPA says “more than 225,000 acres of habitat including coastal wetlands have been protected, restored or enhanced.”

Additionally, over 4,900 river-miles have been cleared for fish passage, according to the EPA.

All that glitters isn’t gold

Not every program has been a success.

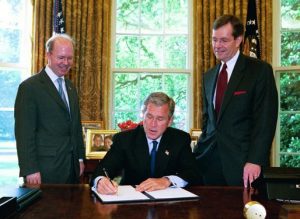

In 2011 following a then-record algae bloom in Lake Erie caused by nutrient runoff from farms, GLRI started to prioritize money to incentivize farmers to use best practices that would minimize runoff.

In simple terms, they were paid to not pollute.

To date, $100 million in GLRI money has been paid to farmers, according to the Great Lakes Commission representing the region’s governors. But results of the program are questionable as Lake Erie’s health has officially declined to “poor and deteriorating” status.

In 2014 a toxic algae bloom that hit Toledo’s drinking water intake pipes caused the city to be without drinking water for three days.

And the program that pays farmers to not pollute “has not been comprehensively evaluated to assess its effectiveness and inform future investments in water quality,” according to the commission’s website.

The commission is in the process of doing that evaluation now.

Great Lakes policy adviser Dave Dempsey says “there should be a moratorium on paying farmers to do what they should already be doing and that’s using farming practices that don’t pollute drinking water.”

Dempsey says, “some of the money should be used to support development of enforceable phosphorus reduction plans from troubled watersheds in the Western Lake Erie basin.”

While at the International Joint Commission, Dempsey was instrumental in developing the commission’s LEEP study that analyzed Lake Erie’s algae problems and made recommendations for remedial actions.

The environmental non-profit Healing Our Waters Coalition is the lead group that lobbies for GLRI funding. The group’s director, Todd Ambs, did not respond to a request to comment on whether GLRI should continue funding that pays farmers to reduce nutrient runoff.

Absent progress on Lake Erie seven years after the EPA made it a priority, legal pressure came from Chicago’s Environmental Law and Policy Center. It now appears Ohio and the U.S. EPA are moving closer to taking meaningful action after recently being excoriated by a federal judge.

In spite of the EPA’s claim to progress on toxic sites, there are five locations including the Detroit River that won’t have contaminated sediment removed until 2025 or later. That’s at least 20 years after cleanup of the first site in the river.

U.S. Representative Debbie Dingell, Photo by Peter Smith via flickr.com

That prompted Michigan Congresswoman Debbie Dingell to say the 2025 date was “unacceptable.” Dingell’s district borders the river and she plans to contact the EPA to express her concern.

Not all Great Lakes problems are funding issues that can be improved by GLRI.

Since Asian carp were discovered at the doorstep of Lake Michigan in 2009 there has been little progress toward implementing permanent infrastructure improvements to keep the carp at bay. Congress has not authorized the Corps to do anything beyond studies.

And implementation of the Obama administration’s Clean Water Rule that would actually prevent pollution to the lakes has been stymied by the courts. Additionally, the Trump administration lead by EPA Administrator Scott Pruitt has moved to roll back the rule.

The public engagement sessions are scheduled for Rochester (N.Y.), Duluth, Milwaukee, Saginaw and Chicago.

The EPA says the proposed plan will be available for public comment later this year.

Featured Image: Photo by Yinan Chen via pixabay.com cc0