From our friends at Bridge Magazine

MICHIGAN CITY, Ind. — About a dozen middle schoolers clustered on a beach on a recent morning — sun shining, a slight chill in the air. Some looked down at the sand. Others at Lake Michigan, its hypnotic waves washing ashore.

Most appeared to listen as a gray-haired, gray-bearded instructor shared a message that bordered on a plea: Too few folks appreciate the dangers of the Great Lakes, whose waters kill dozens of swimmers per year. Too few know what to do when sudden currents whisk them from shore.

To bolster his point, Bob Pratt, the 59-year-old executive director for education at the nonprofit Great Lakes Surf Rescue Project, launched a quiz.

“What do you do if your clothes catch on fire?”

“Stop, drop and roll,” the students answered.

“What number do you call if you have an emergency?”

“9-1-1,” came the reply.

“What do you do if you’re drowning?”

A pause.

“Scream ‘help,’” one boy answered. A girl waved her arms.

“Here’s the thing,” said Pratt. Arm-waving means sinking. Screaming? Not if you’re choking on water. It all happens so fast, he explained. The answer: Flip on your back, float to conserve energy, try to calm down, and then follow a safe path to shore.

A few yards away, a firefighter taught another gaggle of students how to toss an orange life ring to anyone struggling in the water. Across the beach, still more kids learned about lifeguarding from a pair of beach veterans.

For the students of Krueger Middle School in Michigan City, just south of the Indiana-Michigan border, it was a fun, if at times sobering, field trip. For Pratt, a retired East Lansing fire marshal who now leads trainings like this across the Midwest — often camping in his pickup truck – it was another day in his battle against what he calls an “epidemic” of drownings in the Great Lakes.

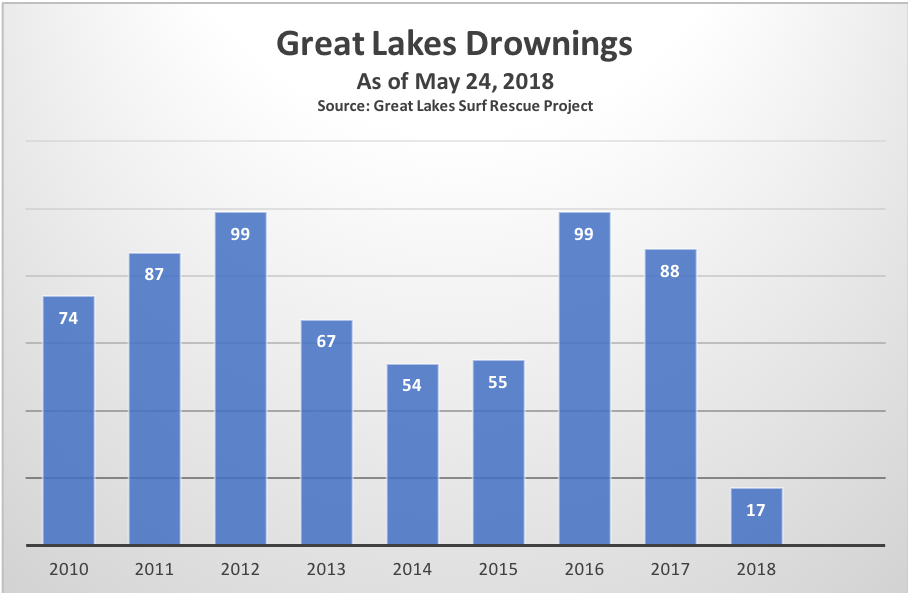

Memorial Day kicks off the unofficial start of summer, and already this year, at least 17 people have drowned in the Great Lakes — four of them off Michigan shores.

Last year, 88 drowned in the Great Lakes, bringing the tally to 640 since 2010, according to according to data gathered by the Surf Rescue Project, the nonprofit that Pratt founded in 2007 and now runs with Dave Benjamin, an Illinois native who became an advocate after nearly dying while surfing in Lake Michigan.

The Great Lakes are “really more like inland seas than they are a lake, and they pose particular dangers,” said Pratt, who lives with his wife in East Lansing but spends long stretches teaching on the road.

Strong and sometimes dangerous currents can form near structures along the Great Lakes, like around this Lake Michigan lighthouse along the shores of Michigan City, Ind. (Bridge photo by Jim Malewitz)

Strong and sometimes dangerous currents can form near structures along the Great Lakes, like around this Lake Michigan lighthouse along the shores of Michigan City, Ind. (Bridge photo by Jim Malewitz)

Pratt, who was named the National Drowning Prevention Alliance’s “Lifesaver of the Year” in 2012, has played a key role in regional efforts to make the Great Lakes safer.

If not a “superhero,” Pratt is certainly a “champion,” said Jamie Racklyeft, who leads the 2-year-old Great Lakes Water Safety Consortium, an Michigan-based umbrella group for researchers and others trying to end Great Lakes drownings.

“He’s been a lifeguard, a fire chief, he’s been a fantastic trainer of all-ages.”

‘So relentless’

Globally, the World Health Organization considers drowning a “vastly neglected area of public health.” And for decades, the same has applied to the Great Lakes, which hold 20 percent of the freshwater on Earth’s surface and have powerful currents.

In some ways, the mammoth lakes are more perilous than oceans, whose salt makes floating easier. Great Lakes waves are typically smaller than those in the ocean, but they come far more frequently, said Pratt. Survivors of near-drownings describe being pummeled.

“The waves were just so relentless,” said Racklyeft, who in 2012 nearly drowned in Lake Michigan while swimming off a beach 25 miles from Traverse City. “They were 4 and 5-feet tall, every five or six seconds.”

Most drowning deaths are preventable, Pratt and other experts say. He’s among those pushing for policies — more life guards and safety equipment on public beaches, more education for kids — to thwart the problem.

“We need to catch up with the education for water safety,” Pratt said.

Diving for data

In an age where Americans with an internet connection have seemingly endless data at their fingertips, Pratt learned the hard way in 2003 that no government agency catalogues drownings on the lakes that touch eight states and two nations.

That was when he drove his son to Grand Haven for some surfing on Lake Michigan. Greeting them when they arrived: U.S. Coast Guard boats and a helicopter scouring the lake in search of a body. The park was closed, Pratt recalled, leaving a small clutch of people on the beach — law enforcement and presumably family members — awaiting news about their loved one who would end up dead.

It wasn’t the first time Pratt, a poor swimmer until taking lifeguarding classes while attending Michigan State University, had witnessed such a search. That day in Grand Haven got him wondering: How many people had drowned on the Great Lakes? Some Googling and other poking around led him nowhere.

“Believe it or not, nobody knew,” he said.

The Centers for Disease Control tracks and categorize all deaths across the U.S., but its data doesn’t shed light on how many happen in the Great Lakes. The National Weather Service tracks Great Lakes incidents specifically related to dangerous currents (12 fatalities, 23 rescues on average each year.)

And Michigan state health data show 125 accidental drownings statewide in 2016 in any water.

Today, Pratt’s group keeps a comprehensive database of Great Lakes drownings. It includes those who die shortly after a rescue — from conditions clearly caused by their struggle in the water – but not obvious suicides. He scours news reports and other official sources for data, and sometimes gets tips from friends or others on-the-ground. Armed with the information, he can tailor his message to those who most need to hear it.

From the data he knows:

- Great Lakes drowning victims are overwhelmingly male — Pratt suspects they’re more prone to showboating or carrying out dares.

- The majority of drownings happen near the shoreline, typically involving bathers, kayakers, paddle boarders or surfers.

- Life jackets save lives. Only seven of the drownings since 2010 involved people wearing life jackets, and most of those were due to cold waters.

Not surprisingly, drownings tend to spike when the weather is warm and waves are high, conditions more likely to drive people to the beach.

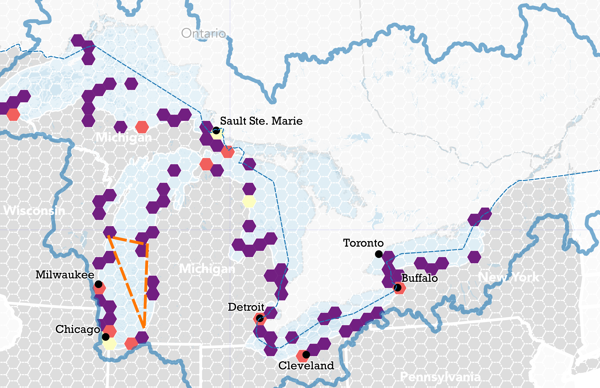

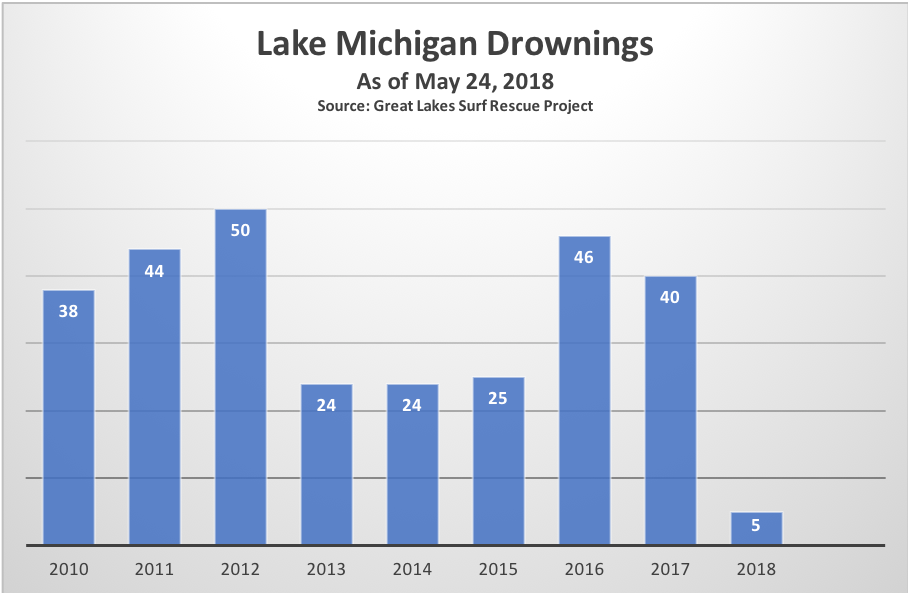

Some 296 of the documented Great Lakes drownings since 2010 were in Lake Michigan, with a significant share along its southern shore — largely, Pratt said, because the lake has so much usable beach and relatively high populations nearby.

That’s 10 times the death toll from the 1975 wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald, the Lake Superior freighter immortalized by Canadian songwriter Gordon Lightfoot. Lake Michigan in each of the last two years has seen 40 or more drownings.

An online relationship

Pratt founded the Great Lakes Surf Rescue Project in 2007, in association with the Great Lakes Surfing Association. As he dug into data, he also trained surfers and attended a slew of conferences.

Along the way, he met Benjamin, a longtime surfer, through postings on an online surfing forum. After organizing a few safety trainings together, they fully teamed up at the nonprofit.

“It’s one of those successful online relationships,” joked Benjamin, who manages projects and handles public relations.

A sign warning of rip currents at New Buffalo Lakefront Park and Beach. (Bridge photo by Jim Malewitz)

A sign warning of rip currents at New Buffalo Lakefront Park and Beach. (Bridge photo by Jim Malewitz)

Benjamin poured his energy into Great Lakes safety after nearly becoming another Lake Michigan casualty in December 2010, shortly after his 40th birthday.

Knocked off his surfboard and fighting a current in 35-degree water that felt like razor blades through his wetsuit, he held onto what he thought was his final breath. But as a whirlwind of thoughts churned in his mind, one memory stood out: an article by Mario Vitone, a sea survival expert.

Benjamin remembered to flip on his back, inflate his lungs and float. About 40 excruciating minutes later, he managed to crawl back ashore.

“After that drowning accident, it’s just like borrowed time,” Benjamin said. “Another way I phrase it is ‘this is what I have left to do.’”

For both men, their work is a labor of love and some frustration. Both believe Great Lakes-area governments should invest more in water safety.

“Millions of dollars are spent each year to bring more people to water, with billions of dollars in return,” said Benjamin. “Yet when something happens, we blame the victim or the parents or caregivers, and we don’t fund anything.”

Bob Pratt (left), poses with Dave Benjamin, his partner at the nonprofit Great Lakes Surf Rescue Project. (Bridge photo by Jim Malewitz)

Bob Pratt (left), poses with Dave Benjamin, his partner at the nonprofit Great Lakes Surf Rescue Project. (Bridge photo by Jim Malewitz)

Neither Pratt nor Benjamin draw a salary. The nonprofit raised $83,000 last year, including the donation of a truck, Benjamin said. This year, it’s holding many of its trainings in Indiana thanks to a $50,000 matching grant from the state.

Benjamin pays his bills through commercial painting, though he says he’s rapidly losing contracts as he spends more time on the road. Until recently, Pratt, who retired from the East Lansing Fire Department in 2012, did lawn care to supplement his income.

That’s partially why, instead of paying for a hotel, he camped out in his truck the Tuesday night before teaching the Krueger middle schoolers earlier this month at the lake he respects so much.

“It’s such a big, beautiful body of water,” he said. “But it’s also so dangerous.”

1 Comment

-

Drownings for Lakes Superior and Huron seem low. Do these include Canadian statistics?