Seven years ago, (May 9 in 2011), Michigan became home to only the 9th international dark sky park in the world. The designation was awarded by the International Dark Sky Association in Tucson, AZ, and required a rigorous application process undertaken by a team of leaders and community members that demonstrated their willingness, through county ordinance, public programming, and personal commitment, to safeguard one of contemporary humanity’s most overlooked sources of imagination and inspiration: natural darkness, and our access to it on public lands by night.

One year after the IDA designation, the State of Michigan passed House Bill 5414, protecting the night sky over 21,000 acres of state park lands for its dark skies. In 2016, that legislation was amended to include several more parks, increasing the amount of state park land now dark-sky protected to 35,000 acres, all of it in Michigan’s lower peninsula.

The Headlands International Dark Sky Park: a sought-after destination

Mysterious beauty of the northern lights over Lake Michigan, Memorial Day weekend 2017, Photo by Samarth H Shivaswamy via Mary Stewart Adams

The Headlands International Dark Sky Park in Mackinaw City became an instant success once the International Dark-Sky Association announced its designation. Further bolstered by rare astronomical phenomena like the Venus transit of 2012, annual eclipses and meteor showers, space station fly-bys and its beautiful location along two miles of undeveloped Lake Michigan shoreline have made it a sought-after destination for tens of thousands of visitors each year.

During the nine years I served as Program Director at Headlands, we received numerous honors and awards, including commendation from the International Year of Astronomy, a sub-committee of the International Astronomer’s Union; the Innovative Programming Award from the Michigan Parks and Recreation Association; the Pure Michigan “Pure Award”; and the first-ever awarded International Dark Sky Park of the Year Award, in 2017. The high level of visibility generated by these awards, augmented by immediate access to information about the night sky that is generated by social media, have also added to the popularity of the Headlands and the state’s dark sky sites, while it also quickened the County leadership’s decision to develop the site with 24-hour restrooms, outdoor seating and staging, as well as indoor programming space and an observatory.

But the story of protecting the starry skies over the Great Lakes state actually reaches back nearly 25 years, to 1993, when Michigan became the first state in the union to prioritize natural darkness as an asset that warranted protecting in its state park system.

The State’s Natural Resources and Environmental Protection Act 451 designated Lake Hudson State Recreation Area south of Jackson as a dark sky preserve, with the intent to encourage and support the already popular nighttime use of the park, and to demonstrate how dark sky preservation and lighting restrictions would not limit other recreation activities and programming within natural landscapes.

Michigan: a super nova in the international dark sky movement

And so Michigan – a state known more for its cars than its stars! – became a super nova in the international dark sky movement.

Since 2011, the International Dark Sky Association has designated an additional 50 international dark sky parks worldwide, yet despite this increase in the amount of protected lands and the level of awareness this raises about the issues of light pollution, research shows that the glow from humanity’s use of artificial light at night is steadily increasing, globally, at a rate of 2% each year. The IDA estimates that roughly one third of all artificial light used at night in the United States is wasted because it’s spilling up into the sky where it’s not needed.

This amounts to a waste of over $3 billion every year in the US alone. Calculated another way, the amount of “pollution” this creates in carbon emissions amounts to over 15 million tons of CO2 released into the environment, and all for light that is not needed. We’d have to plant over 800 million trees annually to offset that amount of carbon emission.

It may seem ironic, but what really matters most in the international dark sky movement is not how dark it is, but whether or not a community can make the commitment to so alter its use of artificial light at night that its activity results in less energy use, which leads to less waste, and, consequently, to a restoration of the star shine and the natural beauty of our environments, which then, by default, supports astronomical research.

Natural darkness is a habitat unto itself

Natural darkness is a habitat unto itself, required for bird migration, nighttime pollination, mating, hunting, and yes, sleeping.

So: let’s zero in on one Great Lake: Lake Michigan, the only Great Lake completely bounded by the US, and consider the potential contribution to this problem of the misuse of artificial light along its 1600 miles of shoreline.

There are an estimated 12 million people populating the 60 cities along this great body of water, which means that along the shores of Lake Michigan alone, we are potentially contributing $124 million to the $3.3 billion waste being caused by a misuse of artificial light at night each year. This equals about 2.5 million metric tons of greenhouse gasses dumped into the environment.

Further, there are an estimated five million birds representing 250 different species that migrate through the Lake Michigan region each year, along its shores and over this land. However, the lights emanating from the skyline of Chicago, because of the city’s location along these same shores and migration routes, causes more bird deaths every year than in any other city nationally.

Navigating by the stars and hungry after flights from as far away as Peru, the birds arrive on Lake Michigan’s shoreline in search of food. There, the twinkling city and its canyons become a death trap.

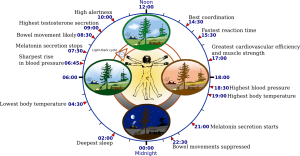

To facilitate thinking about the significance of natural darkness, consider that the environment by day and the environment by night are two different things, even when they are geographically coincident. From those of us who would be stewards of the whole, the daytime environment requires a different engagement than does the night in the same environment. And this difference between daytime and nighttime in the environment is true in human consciousness as well, but because we are literally asleep to the role of the dark in our health and well-being, it is easy to miss its significance.

Stewardship of the night sky is about place-making

Medical research now shows that artificial light exposure at night interferes with the human body clock, known as the circadian rhythm, and can suppress the body’s production of the hormone melatonin. Melatonin is the sleep hormone, and its suppression can lead to sleep disorder. Further, sleep disorder is connected to almost every major illness that plagues our population, and academic studies now reveal that there is an increase in certain kinds of cancers by night shift workers. All of this (forgive me) sheds light on the reality that the effective use of artificial light in our environments is about so much more than our being able to see the stars ~ it’s about habitat stewardship, energy resource management, and human health and well-being.

And in Michigan, where tourism is one of our top three industries, stewardship of the night sky is about place-making, about enhancing the natural beauty of our environments and communities by day, and by night.

Any theater manager can tell you that the way to create environments on stage is not by costuming or set design – it’s through lighting, and the same can be said for our streetscapes and businesses and campgrounds and wilderness areas.

Light can make or break the mood and enhance or hinder the experience.

Historically, some of the highest achievements in the history of humanity have resulted from an attempt to know ourselves in relation to the celestial world around us. Think of the Great Pyramid at Giza, so built in 2560 BCE that it aligned to the star Thuban in the constellation Draco, because that was how to properly determine the place for a ceremonial site where would be conducted the coronations, the initiations, the burials; or even Stonehenge, built earlier than Giza, in 3100 BCE, which essentially served as a megalithic clock aligned to the Sun at its solstice moments so as to safeguard the human being in sacred ceremony by knowing when to perform certain deeds; or even the Very Large Telescope array in the Atacama Desert of Chile, built in the 1990s and aimed skyward to find exoplanets and evidence of blackholes ~ each structure aligned to the stars, though built centuries apart from one another and according to the technology and understanding of their own time, dramatically revealing that human beings have been reaching toward the same thing throughout history, regardless of gender, age, or nation.

“To know ourselves in relation to the stars”

This singular striving to know ourselves in relation to the stars has informed everything from social organization and religious observation, to agricultural practice and scientific research, and has been regarded in every age as the highest knowledge.

And while the hard science of astronomy dominates the contemporary understanding of our celestial environment, high achievement has likewise been produced in the art, literature and poetry inspired by the night. Vincent Van Gogh gave us an example of the necessity of regular exposure to the star shine when he said he knew nothing with any certainty, but the sight of the stars made him dream. What if we lose our sight of the stars? Do we lose our ability to dream? And what of losing our dreams? Certainly, it seems this would have mattered desperately to one of the greatest minds of the 20th century, Albert Einstein, who said: “When I examine myself and my methods of thought, I come to the conclusion that the gift of fantasy has meant more to me than my talent for absorbing positive knowledge.”

In the poet’s world, star shine is necessary to a healthy unfolding of human destiny, especially as expressed in the ancient mythology regarding the constellation Lyra, which rises up in May each year. Fortunately, this constellation region is easy to identify even in the most light-polluted areas because of the bright star Vega. To ancient cultures, the constellation Lyra represented the lyre of Orpheus, the stringed instrument that was like the soul of the human being.

For the stargazers of those ancient ages, it was believed that souls were guided to one another by their greater destiny, which they were called to through the sounding out of a note on this mighty cosmic lyre. What comes of not knowing these stars, and to not “hearing” this sounding out? Or in other words, what is it that we really lose when we lose the night?

Perhaps, we lose our way.

Featured Image: A colorful star-forming region as seen from the Hubble Space Telescope, Photo by nasa.gov via wikimedia

Don’t have dark enough sky in your area and wonder how you can affect positive change in your neighborhood and community?

You could start by:

joining one of Michigan’s 22 registered astronomy clubs

Eager stargazers can find exceptional sites and dedicated communities throughout the Great Lakes region, including: At Headlands International Dark Sky Park

There are six night-sky protected state parks in Michigan

Newport State Park in Wisconsin’s beautiful Door County, designated an international dark sky park in 2017

Starry Skies Lake Superior in Duluth, Minnesota, which hosts a terrific event about all things dark sky every year in September

There is an Aurora Summit in Two Harbors, Minnesota, for learning how to catch, and capture the most sought-after phenomenon in the sky, the Northern Lights

There are also internationally-designated dark sky parks in Ohio and Pennsylvania, at Geauga Observatory Park in Geauga County, Ohio and Cherry Springs State Park in Pennsylvania

Attend one of the Michigan’s popular star parties, like the Great Lakes Stargaze in Gaylord, now in its 16th year on September 6-8 in 2018

or Astronomy at the Beach at the Island Lake State Recreation Area near Kensington Metropark in Milford, Michigan, September 14 and 15 in 2018

You can also attend a program at one of Michigan’s 14 planetariums, or visit one of the Michigan’s ten public observatories.

Every year in April, Michigan State University hosts Statewide Astronomy Night with partners throughout the state.

And right in your own backyard, you can host a Perseid Meteor Shower party or a friendly lights-out challenge with your neighbors or a neighboring community ~ this shower peaks very year in August between August 11 and 13, and in 2018 is coincident with a New Moon.

Another idea: take a night sky photography class with an expert, Shawn Malone in Marquette, Michigan, aurora photographer extraordinaire:

Jump a ride on an evening sky cruise on balmy summer nights along the Straits of Mackinac in Michigan with Shepler’s Ferry Service and dark sky advocate Mary Stewart Adams

Join the International Dark Sky Association

Active dark sky community initiatives:

Michigan Dark Skies, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor

Northport Energy Dark Sky Committee, Northport, MI

Negwegon State Park Friends Group, Harrisville, MI