Opening a new potash mine in Western Michigan would bring almost 200 jobs and billions of dollars to the state’s economy.

It would also require more water to be withdrawn at a location not far from the spot where Nestle is already withdrawing water at a rate that allows the company to package 4 million bottles of water a day.

And it’s the latter that is casting a spotlight on a family-run operation with big plans for a Michigan-based company that would deliver a product large farms depend on and often can’t get enough of.

First: what’s potash and who uses it? It’s a mined or manufactured type of salt that contains potassium in a water-soluble form. The name is a derivative of “pot ash”, which refers to plant ashes soaked in water in a pot – that’s the way people obtained a product like this a century ago.

Potash is a type of fertilizer and a potassium compound which is in great demand in China, the U.S. Brazil and India. It creates what many farmers say is higher and more efficient yields of major crops like corn, wheat and vegetables.

According to the CEO of Michigan Potash, Ted Pagano, there are only about 10 major potash mines across the world.

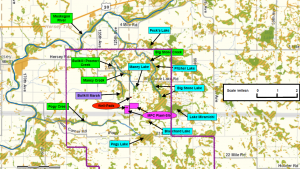

And he’s hoping the next potash mine will be located southwest of Evart in Michigan’s Osceola County.

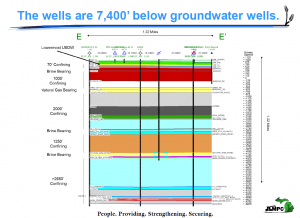

Pagano says here’s how it works: a potash mine uses fresh water to create a hot brine that then dissolves potash under the ground. After the potash is brought to the surface and separated, the left-over waste water is injected deep into the ground.

Pagano tells Great Lakes Now the water supply in the area where he wants to put the mine would not be in danger. He says, “Michigan is blessed with a tremendous amount of good water sources and strong aquifers throughout the entire state. And, in particular, because we’re accessing water that is so deep, it doesn’t have the actual direct connections to streams.” He says. “There’s virtually no chance of any adverse impact to any water surrounding this soil.” He says Michigan Potash would be “a small consumer of water in this particular area.”

A request to draw 725 million gallons of water a year

There are many hoops to jump through to make the mining operation a realty. But one big hurdle has been crossed, and that’s the request to draw 725 million gallons of water a year from the Muskegon River watershed.

Great Lakes Now wanted to find out more about what actions the company had to take to get approval from the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) for this water withdrawal request which is three times what Nestle takes out of the ground in the same region.

Turns out the approval happened on line – with the click of a button and in a matter of minutes. Michigan Potash didn’t even have to consult with a human being at MDEQ throughout the water withdrawal approval process.

Jim Milne is Supervisor of the Great Lakes Shorelands Unit of the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality’s Water Resources Division. He tells Great Lakes Now that for Michigan Potash to get approval to withdraw water for the planned mine “ Two registrations were made using the on-line Water Withdrawal Assessment Tool: registration ID 4535-201610-54 for 1,000 gallons per minute on October 24, 2016, and registration ID 4935-20179-2 for 380 gallons per minute on September 15, 2017. “

Milne explains, “The Water Withdrawal Assessment Tool is an on-line screening tool that provides an answer to the user within minutes. If the proposed withdrawal is able to be authorized by the tool, then the user can print a registration receipt without having to wait for a formal approval from the DEQ. If the proposed withdrawal doesn’t pass the tool, then the user must request a site-specific review by the DEQ before being able to put the withdrawal into operation.”

Milne says, “These two wells passed the Water Withdrawal Assessment Tool and were registered without requiring a formal review and approval by the DEQ.”

Milne says, “The Water Withdrawal Assessment Tool uses 3 models: 1) a regression model that estimates the stream index flow (i.e., the 50% stream flow value during the lowest flow months, typically August or September) based on long-term stream flow data from a network of stream gages; 2) a model that estimates the impact on fish populations from stream flow depletions; and 3) a groundwater model that estimates the stream flow depletion caused by pumping a well.”

Michigan Citizens for Water Conservation opposes the mine. So does Jim Olson, an environmental attorney and water law expert at FLOW in Traverse City.

Jim Olson, Founder & President, courtesy of flowforwater.org

Olson tells Great Lakes Now, “The Michigan Constitution and legislature through the Michigan Environmental Protection Act put an end to the boom and bust history of conservation and destruction, and made protection of air, water and natural resources paramount. The meaning is quite simple, every inch of our soil, forests, fields, wetlands, cold, clear water creeks, streams and lakes are not up for grabs just because someone wants to come into Michigan and remove minerals or deposits like potash.”

Olson says Michigan Potash should not be allowed to go forward with the planned mining operation until it can prove there will be no environmental damage incurred by the mining and by using the millions of gallons of water it needs to extract potash from the site in Osceola County.

Olson explains, “The amount of water and injection of wastes is unprecedented in Michigan’s rural central and north country. The last thing Michigan should and can do is unleash another era like the slaughter of white pine forests. The water withdrawal and loss of massive groundwater and the effects on wetlands, creeks, streams, farming, wildlife – our paramount public water and natural resources—must be fully evaluated, understood, both immediate and long term effects now, before any action is taken. The state has a duty under its environmental and water law to do so, and until this is done there is no constitutional or legal property right for the company to proceed. “

65 Billion Dollars a Year to Michigan’s Economy

Some estimates are that the potassium-rich mineral salt a mile and a half under the ground in Osceola County could be worth more than 65 billion dollars to Michigan’s economy. It would not only produce potash, but table salt, too.

Michigan Potash CEO Ted Pagano says building the mining and processing facility will cost about 700 million dollars.

Nick Schroeck, director of the Transnational Environmental Law Clinic, courtesy of Wayne State University

Nick Schroeck is Director of the Transnational Environmental Law Clinic at Wayne State University Law School. Schroeck tells Great Lakes Now, “The main concern with solution mining of potash is the large quantity of water that is withdrawn and then contaminated. Here, we’re talking about a withdrawal of over 700 million gallons of groundwater annually. Even if they recycle some of the water, that large quantity of a withdrawal will have impacts on the local groundwater aquifer. The groundwater that is contaminated, after the solution mining process, will have to be disposed of in underground injection wells. The contaminated water, or brine, can cause serious problems if it is spilled on the surface. The contaminated brine water can cause significant harm to wetlands, rivers, lakes, and streams if there is a spill. And Michigan’s DEQ likes to tout how safe underground injection wells have been in the state, but every time you add more of these injection disposal wells, whether it is for contaminated brine water or water contaminated from fracking or other processes, you run the risk of one of these storage sites failing and causing severe environmental damage.”

Schroeck says Michigan’s rural areas in need of jobs are often targets for mining companies.

“Michigan has a history of mineral extraction for economic development. Sometimes the projections for jobs and increased economic activity come true, at least for a while. Yet if we look at the ghost towns in the Upper Peninsula from the copper mining boom, it’s a reminder that the jobs don’t always stick around, but the environmental impacts are lasting and can be irreversible.”

Michigan’s Water Withdrawal Assessment Tool has won awards. It is often praised by agencies and environmentalists across the country.

But in the case of Michigan Potash, many questions are being raised about the ease in which a major corporation was able to get the go-ahead to draw what amounts to 1.98 million gallons of water a day.

The MDEQ’s Milne explains, “The Water Withdrawal Assessment Tool predicts the amount of stream flow depletion caused by pumping the well and the risk of that well causing an adverse resource impact to fish populations and stream flow. The Water Withdrawal Assessment Tool makes some conservative assumptions, including assuming that the aquifer used by the well is connected to the stream and it applies a safety factor of allowing only 50% of its estimated stream flow to be available for use until the DEQ is able to do its own stream index flow review. In the case of the Michigan Potash wells, they were the first two large quantity wells proposed in the two affected watersheds so the 50% safety factor was still in effect. “

Milne says, “The water will be extracted from two wells, both of which are pumping from an aquifer 215’ below grade. Michigan Potash proposed to pump these wells continuously (24/7/365) for a maximum total annual withdrawal of 725,328,000 gallons per year. Michigan Potash will recycle the water through multiple rounds of solution mining before disposing of the waste water into deeper geological formations that are not connected with the Great Lakes Basin. The wastewater cannot be returned to aquifers that are connected to the Great Lakes Basin or directly to streams because the brine concentrations are harmful to aquatic life and are unfit for drinking water.”

Several residents in the area where the proposed mine would be built made their voices known at recent public hearings. Hersey resident Doug Miller says the MDEQ is understaffed and is using old outdated data. Miller says, “The DEQ has accepted, as documentation from Michigan Potash, studies undertaken by PPG industries 35 years ago that were prepared for a site 2 miles away from the Michigan Potash site in question.” In addition, Miller says, “Section 25 of Hersey Township, which lies at the heart of Michigan Potash’s proposed mining area, has never undergone any sort of hydro-geological assessment at all.”

W.W.A.T. does not evaluate the impacts of the wells on wetlands or aquifer levels

Great Lakes Now asked the MDEQ’s Jim Milne if he could definitely say this water withdrawal request from Michigan Potash won’t drain the aquifers or harm the wetlands. He answered, “The Water Withdrawal Assessment Tool (W.W.A.T.) does not evaluate the impacts of the wells on wetlands or aquifer levels, only stream flow and fish populations. DEQ field staff evaluated the proposed well locations and had some of those locations moved to avoid having their construction impact wetlands. Michigan does have an aquifer dispute resolution program, Part 317 of the NREPA, that addresses impacts to small private wells from high capacity wells.”

Milne says, “The Nestle’ wells are on the opposite side of the Muskegon River from the Michigan Potash wells. Nestle’s and Michigan Potash’s wells won’t affect each other because groundwater in the region discharges to the Muskegon River. Either Nestle’s or Michigan Potash’s wells would cause water from the Muskegon River to flow into the underlying aquifer(s) if their zones of influence were to reach that far, which they won’t. “

Great Lakes Now asked the MDEQ’s Jim Milne to give us a comparison of some of Michigan’s biggest water withdrawers. He said, “The most recent annual water use data available is from 2016. AK Steel Dearborn Works is the biggest water user in Michigan, 229.3 million gallons per day. Pharmacia and Upjohn Company LLC is the #8 water user at 18.1 million gallons per day. The proposed Michigan Potash wells would be #47 at just under 2 million gallons per day. All 4 locations for Nestle’ Waters North America is #70 at 1 million gallons per day. Cargill Salt in Hersey is #159 at 500,000 gallons per day.”

So – is it a done deal?

Michigan Potash’s Ted Pagano says the actual mining operation is a long way off. The Environmental Protection Agency approved Michigan Potash’s well permits in 2016 and 2017. Now that the company has secured the right to withdraw 725 million gallons of water a year to process the potash, there are many more steps to be followed that include getting permits for pollution discharge, wetlands destruction and erosion control.

Pagano says if he gets the green light for all requests and permits, Michigan Potash could break ground in the coming year, but the mine most likely wouldn’t start operating for at least three and a half years.

(Editor’s note: watch our documentary about water withdrawal “Tapping the Great Lakes” which premiered on DPTV March 26th, 2018)