This story originally appeared on Great Lakes Today and is republished here with permission.

Part 1 in a series on environmental justice issues in the Great Lakes region.

Would you want an industrial waste dump near your house? Probably not. But across the country, environmental hazards like waste dumps tend to be located near minority communities.

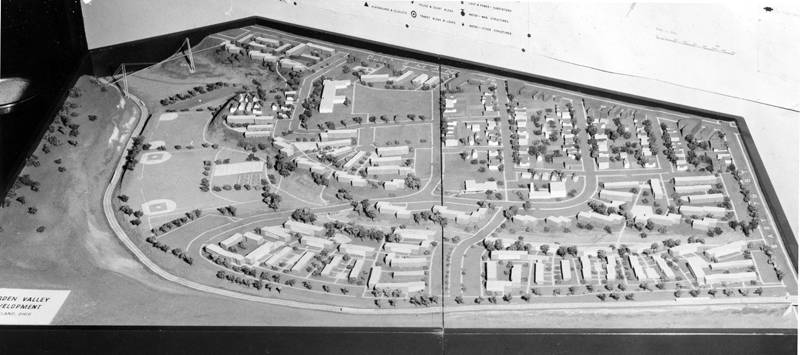

Marion Motley Playfields is a park on Cleveland’s east side. Named for a local pro football star, it has grassy fields, baseball diamonds and hills.

But those fields hide a troubling history. Before the park was created, parts of the property were used as a storage yard for a brick and tile plant, and a stream became an industrial sewer.

Vera Brewer recalls playing there as a child, with “tires, old pieces of furniture, and cans to throw and toss.” At the Garden Valley Neighborhood House a few blocks from the park, she shared a memory that still makes her feel guilty.

One day, Brewer and her cousins wouldn’t go back to her aunt’s house when called. So the aunt came to get them — and stepped on a rusty nail.

“Had it been that we were not playing in the dump, she would’ve never had her foot injured,” Brewer said. “That’s where we played, that’s where everybody played. We didn’t know not to be there because of contamination – our mindset was on enjoying life.”

The area was transformed into a park in the 1960’s. Its past was covered up and the stream filled with material from Republic Steel.

On a recent sunny afternoon, James Miles walked through the park, reminiscing about times spent there as a kid.

“We used to have a ball over here, me and my siblings and all of our friends over here,” he said. “We used to call it ‘the dump’ – but it’s a field.”

Today, environmental pollution remains. A report last year revealed metals in the ground, including arsenic and lead.

The city’s capital projects director, Matt Spronz, says those chemicals – along with many others – existed in soil samples and ground water at levels higher than state standards.

“Back in those days, when people filled in property, whether it was in their backyards or whether it was anywhere else, there was no [U.S.] Environmental Protection Agency or Ohio EPA, and the materials they put in to those areas were unknown at the time,” he said.

Now officials plan to put a two-foot soil barrier over the ground to keep kids safe from the chemicals. Playing in lead-contaminated soil can hinder brain development, especially for children.

The Cleveland park illustrates a much broader problem. There are properties all over the country that were once landfills, dumps or uncontrolled toxic waste sites.

In Chicago, for example, there was a “toxic doughnut” of landfills and industrial facilities; it’s finally getting cleaned up, but legacy pollution remains. In East Chicago, Ind., it’s the USS Lead site, one of the most contaminated in the country.

These sites tend to be located in minority communities, according to reports commissioned by the United Church of Christ.

Texas Southern University professor Dr. Robert Bullard, co-author of one of those reports, said, “Racism trumps income and class when it comes to many of these environmentally facilities that historically have gone through the path of least resistance.”

Nationally, the EPA reports that 45 percent of people of color live within three miles of a Superfund site – places highly contaminated by hazardous waste.

Living near these sites can bring lots of problems: odors, noise pollution and depressed home values.

And there are potential health impacts. While it’s difficult to prove a direct connection to serious conditions like cancer, scientists suspect living near landfills or waste sites can make people sick.

While there are thousands of Superfund sites across the country, there are likely more like Marion Motley Playfields – not as contaminated but still unsafe.

Miles is happy the city is working to clean up the park.

“If there’s any kind of contamination down here at all, I’m more than excited to see it finally getting the attention it needs around here,” he said.

Meanwhile, other communities continue to fight to expose the unseen – but lasting – impacts of the region’s industrial past.

Coming in Part 2: Minority commmunities are burdened by air pollution — and high asthma rates.