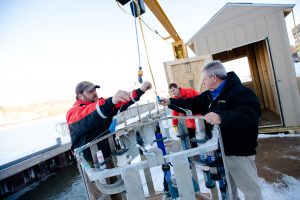

Buoy deployment. Photo courtesy Sarah Bird, Michigan Tech.

An interview with director of the Great Lakes Research Center, Dr. Guy Meadows

(Note from DPTV’s Great Lakes Bureau Chief Mary Ellen Geist: On September 18th, 2017, Michigan’s Pipeline Safety Advisory Board voted unanimously to recommend that the state contract a team of academic experts lead by Dr. Guy Meadows to complete a risk analysis study on the safety of Enbridge’s Line 5 pipeline which runs underneath the Straits of Mackinac. Dr. Meadows stepped down from his position on the board to complete this study which will take six months. Dr. Meadows agreed to give an interview to Great Lakes Now to explain more about his background and what we can expect from a pivotal study that may wind up influencing major decisions about the fate of the Enbridge-owned pipeline in the Straits of Mackinac.)

GLB: Thanks for talking with us. First, your title.

Dr. Meadows: I’m Director of the Great Lakes Research Center at Michigan Technological University.

GLB: Are you from the Great Lakes Region?

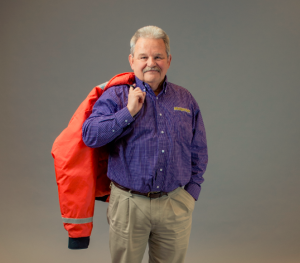

Dr. Guy Meadows, Director of the Great Lakes Research Center, courtesy – Sarah Bird

Dr. Meadows: I grew up in the city of Detroit – a product of Detroit public schools. I went to Michigan State University and worked for a professor there as an undergraduate who was doing studies for the Navy about how waves transformed across natural beaches. I really enjoyed that work. When I graduated as a Mechanical Engineer from MSU, I went to Ford Motor company, and fortunately, I was assigned to rear axle shaft design. And that pushed me to go back to college! So, I got a hold of that professor.

GLB: In other words, you owe your career to Ford Motor company assigning you to rear axle design?

Dr. Meadows: Pretty much! I come from a long list of family members who work for Ford Motor company. I tried to follow in that footstep, but the concept of being paid to work on beaches and study waves was just too big of a pull!

GLB: Where did you do your graduate work?

Dr. Meadows: I went back to Michigan State to get a master’s degree in mechanical engineering, focusing on heat transfer and fluid mechanics with a minor in applied math. And then went on to Purdue University, following that same professor when he made that move, to work specifically on coastal research.

GLB: This was all Navy-funded research?

Dr. Meadows: Yes, and all this work for the Navy was on the Great Lakes. The Navy recognized long ago that our wave climate is very severe. The Great Lakes are an excellent place to study storm waves and how they transform beaches, and how difficult it is to put people across beaches and big surf. So, I graduated with my PHD in that field and then got hired by the University of Michigan straight out of my PHD, and spent 35 years there as a professor of physical oceanography In the College of Engineering at the University of Michigan – all Navy-funded research.

GLB: Explain more about how the Navy uses this research.

Dr. Meadows: Our wave climate here in the Great Lakes is very severe and not altogether different from many places all over the world where big waves are prevalent. The safety of their people, transport of their people and equipment across beaches, amphibious landings, things of that nature are why they do this research.

GLB: And now you are heading up a state-of-the-art lab that researches the Great Lakes. How did this come to be?

Great Lakes Research Center, courtesy – Sarah Bird

Dr. Meadows: In 2012, Michigan Tech created their Great Lakes Research Center and they asked me if I would come up and help start it. The University has made a huge commitment to the Great Lakes. They added a new super computer to the building, and they created six new faculty lines devoted to Great Lakes research. It’s a huge commitment, and it is quite an honor to come up and help start this organization. We are now in our 5th year.

GLB: How did the Great Lakes Research Center develop?

Dr. Meadows: The University did a strategic planning exercise and realized that working on water united a number of strengths the University already had. So, they pushed with the state legislature for the creation of this Great Lakes Research Center. The design of the center is that we bring people in from very different disciplines, everything from water policy, engineers, biologists, fisheries research people – all of them work on very tough problems that face the Great Lakes. We do this from a multidisciplinary point of view. Within the Great Lakes Research Center is about 25 faculty and graduate students that do that kind of work and want to do the collaborative things that are bigger and more important than they could do from their own departments. Some of our work in the Straits of Mackinac has come from that very approach.

ACT Under Ice Study, courtesy – Sarah Bird

GLB: Do students actually attend classes there at the center and get degrees from the center as well?

Dr. Meadows: We do have a classroom which is very helpful but the people that are part of the Great Lakes Research center are actually faculty in their own departments. So, the degrees are all generated through their own departments. It provides an opportunity to have people in the same place with the same vision and goals to work on collaborative things.

“The Big difference between the ocean coasts and the Great Lakes: we drink the water!”

GLB: Do you also work with other research facilities and with government agencies?

Dr. Meadows: We work very closely with NOAA. A couple of examples: with NOAA, and the fact that we have this supercomputer cluster right here in our building, we are working on the next generation of predictive models for the Great Lakes. And the Great Lakes, because of the dedicated work of NOAA, is probably a decade ahead of our partners on the ocean coasts, because there’s one major difference between how the water flows and the ocean coasts and the Great Lakes and that is: we drink the water! NOAA has started these massive programs to be able to accurately tell Cleveland, Chicago, Detroit, and other cities when to shut own municipal water intake if there’s a shipping disaster, harmful algal blooms or some other contaminants in the Great Lakes. So, we work very closely with NOAA to advance that predictive capability.

One of our strategic hires of six new positions was one of the creators of the new modelling framework, so we have a tremendous capability to do predicative models. And then the supercomputer allowed us to do the Lake Michigan/Lake Huron model together, which means we now numerically know there’s a Straits of Mackinac.

And we can predict flows through the Straits. It’s something we’re working on, and NOAA is working on, very diligently. We also have an environmental monitoring buoy that we put in in 2015 in the Straits of Mackinac which provides to the general public real time – once every ten minutes – the complete flows throughout the Straits of Mackinac from the surface to the bottom, as well as waves and winds. It’s one of 14 buoys that exist across the Great Lakes. But this one in the Straits of Mackinac really provides data to verify these models. And in the event that something were to happen in the Straits of Mackinac, it’s the only real direct instantaneous measurement with what the flows are doing, and we are learning that they are extremely complex in the straits.

“A Sleeping Giant on the Bottom of the Lake”

GLB: Have you been aware for a long time that the Line 5 Pipeline Exists?

Dr. Meadows: I have been, but it was one of those things that was not in the news. There were absolutely no problems since it was deployed in 1953, the year before the Mackinac Bridge was built. It was kind of a sleeping giant on the bottom of the lake that no one thought about. One of the things that we’ve been working on with Enbridge is to reduce the time between measures of how the bottom changes around the pipeline. And we are operating a fully autonomous underwater vehicle with a sonar system to die for.

Autonomous Underwater Vehicle, courtesy – Sarah Bird

It is a state-of-the-art highest resolution sonar, and we can fly that thing with nobody attached to it for up to 8 hours at a time. We program that with Enbridge to fly, offset from the pipeline, about 45 feet or so and 15 feet above the bottom, and provide very detailed sonar images of how the terrain around the pipeline changes. And prior to that by their requirements with the Department of Transportation, they needed to survey that pipeline using humans once every three years. And they literally put divers on the bottom with tape measures and went along the pipeline and measured what the spans were. With our sonar system, we can do that in about two hours now for each of the pipelines.

GLB: What is the financial arrangement between your research center and Enbridge?

Dr. Meadows: Enbridge entered into a research grant with our university to come up with this advanced technology. We developed that technology and then they transferred it to Enbridge to their commercial side and they run it now. You could do that every day if you chose to instead of every 3 years. We did a very in-depth engineering analysis of how accurately could you measure this way, and the answer was quite accurately. We did the standard scientific approach: multiple repetitions in a variety of conditions. The currents in the Straits are amazingly complex and it’s fascinating from a science point of view as well as an operational side.

GLB: What are some other places we can we actually see the results of some of your research, besides the underwater vehicles that are used to examine the Line 5 pipeline?

Buoy Deployment, courtesy – Sarah Bird

Dr. Meadows: What is really cool is, as I said earlier, we have this buoy in the Straits of Mackinac that every 10 minutes measures the currents from the surface to the bottom, and that data is totally available to all the general public every 10 minutes. You can look at it right now. Just go to uglos.mtu.edu which is our public website. There will be 14 buoys that show up there. The one in the Straits, the buoy you’re looking for, is 45175, and if you just click on the little diamond and it will bring up the last 10 minutes of data and it will show you how the currents vary. And right now, this week, they are cooking through the Straits! They are going back and forth. Every day and a half, they switch from going into Lake Huron to going into Lake Michigan. They are different on the surface than they are on the bottom.

GLB: Have the currents in the Straits always been this varied?

Dr. Meadows: There is a 1679 account by a French fur trader paddling his canoe across the Straits of Mackinac, saying it’s the craziest place on earth he’s ever seen, with the currents flowing one way on the Upper Peninsula side, and totally the opposite way on the Southern Lower Peninsula side, and with this buoy we’re seeing the same thing! We can see flows at the surface going into Lake Michigan, for example, and flows deep down going the other way, so it is amazingly complex.

GLB: When you tell me about the strength and complexity of these currents, it does make me wonder if this is the best place to put a pipeline that transports 23 million gallons of oil a day.

Dr. Meadows: We have learned this new information about the Straits in recent years, long after the pipeline was put in place. And frankly nobody wants a spill to happen, including the pipeline owners. But there is a tremendous amount of infrastructure crossing the Straits of Mackinac: power cables, communication cables, the bridge itself, so there is an area where we think more monitoring is called for. And we have now – we’re finding out all this fantastic stuff from a buoy at one location – but just think if we had several buoys across the Straits, or better yet, bottom-mounted instrumentation that was cabled to shore so we could see all this stuff all year, and not just during the navigation season. Because the big drawback with buoys is that they come out of the water when things start to freeze up, and the same with all our research ships. So, another thing we’re working on here at the Great Lakes Research Center is advanced technology to provide all-season monitoring in the Great Lakes, and not just during the navigation season.

GLB: How did you become part of the Pipeline Safety Advisory Board?

Dr. Meadows: I was asked by the Governor to be on it because of my background, some 40 years of working on the Great Lakes and specifically working in the Straits of Mackinac.

So, my seat on the Pipeline Safety board is representing all Michigan universities not just Michigan Tech, and trying to keep them apprised of all the decisions being made by the Pipeline Board Safety Advisory Board and things of that nature, and making sure they know when there’s something that universities can contribute to. I make sure I distribute important information to all public universities in Michigan. There are about 20 people on the board and each one represents a large constituency just as I do. There are environmentalists, representatives of the pipeline industry; there’s a representative from the native American community. It’s a very diverse group. It’s a humbling experience. These are top people in their fields from all across the state; from MDEQ, to the DNR to Michigan Energy.

GLB: I’ve attended recent Pipeline Safety Advisory Board meetings, and when there is a public comment period, it is very emotional.

Dr. Meadows: Yes, it is, and I think that shows that people in Michigan care very deeply about the environment and the things we do. It’s painful at times to see how upset people are, but I think it’s very valuable input by the general public, and we take it very seriously. Our effort now in this new activity is to provide data-driven facts to the board so they can pass those on to the state.

GLB: And now you are leaving the board to head up a team of scientists to analyze the safety of Line 5. Was this a surprise appointment?

Dr. Meadows: No, I was contacted by co-chair of the board, Valerie Brader, about a week before the announcement, and she asked if Michigan Tech would be interested in taking on this awesome responsibility and leading a team of universities from across the state to take on this risk analysis . (Note from GLB Chief MEG: the original risk analysis report that was to be completed by July was thrown out due to conflict of interest concerns involving Enbridge.) We at the Advisory Board are the ones who came up with the scope of the work for the alternatives analysis and risk analysis, and we were very comprehensive. This goes back to the diversity of the board itself. There are many, many angles that need to be represented in this scope of work. It is daunting! SO: my first reaction was “Oh my gosh!” Then we engaged in conversations with my boss and with the Vice President for Research, and the President of the University, and we collectively decided this is something Michigan tech cannot walk away from. We are uniquely positioned because of our past research on the Great Lakes and the Straits and and the currents, and we really do need to lead this, and supplement it with experts at other universities. So we decided to take this on and the meeting occurred and it was unanimously voted upon and we have accepted this challenge.

GLB: How much money is involved?

Dr. Meadows: The money that is set aside is the money that was originally set aside for risk analysis that failed because of the conflict of interest. It’s somewhere between 650 and 750 thousand dollars. The other company that was chosen was a Norwegian company.

Personally, I had reservations of having a company that is not familiar with the dynamics of the Great lakes running the show.

GLB: So now – YOU’RE running the show!

Dr. Meadows: To the extent possible. The University leadership has given me the green light. They know that somebody has to be responsible for every crumb of this thing. And that guy is me!

“What is the worst-case scenario?”

GLB: It’s a huge responsibility, and a possibly controversial position to be in.

Great Lakes Research Center Team, courtesy – Sarah Bird

Dr. Meadows: We are sticking to the facts. Our goal is to provide unbiased scientific information so that decision-makers are armed to make the best decision possible. We are not going to make recommendations. We are not going to let personal opinions get in the way. We are providing the facts: what is the worst-case scenario? Where will it go? How fast will it get there? How much will evaporate into the atmosphere? What is the magnitude of the impact on beaches, fisheries, wetlands, and everything that goes on in the Upper Great Lakes which could be affected? And we will assess this to the best of our ability with our team and with the help and support of all of Michigan’s Universities.

GLB: Is your team assembled yet?

Dr. Meadows: We’re in the process of doing that. What we thought was the most powerful way to reach out is to have our Vice President of Research write to his counterparts at all 15 Michigan Universities and ask other Vice Presidents of Research to distribute the request and the scope work defined by the Pipeline Safety Advisory Board and to have faculty that have subject matter expertise fill out the form and express an interest. We’re collecting those now. And beginning to formulate the teams.

GLB: How many teams will there be?

Dr. Meadows: There are nine major areas of the scope of work. We will have a senior person responsible for each of those nine areas. Then, depending on the area and what that team feels is necessary, there will be other people who will contribute to those areas. So, for example, one area would be environmental impact: there’s wetlands, beaches, fisheries and worst case spills and all types of areas, and there would be a lead person for each of those areas, and then they would try to keep this within that fixed amount of money to produce a comprehensive report within the desired timeline of 6 months.

GLB: Will most research be in the lab, or will the scientists be visiting actual sites along the shoreline?

Dr. Meadows: I think it takes a combination of both. We are creating a giant Geographic Information System (GIS) that we can share, that will have satellite maps for each section of beach, each foot of beach; is this a sand beach, wetlands, or rock beach, what is it? Researchers might want to visit the site if they’re not familiar with it. There’s some of all that involved.

GLB: When do you think the public might be able to see the finished report?

Dr. Meadows: The state would like it completed in six months after we are under contract. The first step: we need to, just like everybody else, create a proposal. So, we are building the team now, the team will write the proposal to the state, then the state will evaluate it just like they did with the other risk and alternatives analysis. There will probably be some back and forth about our methods and how we plan to approach this, and then ultimately we will have the contract, we hope by January 1, and then we’d be finished by the end of June.

GLB: Is this realistic, and can you do the research you need to do in the winter, when there’s ice and snow?

Dr. Meadows: Yes, we can do this. There’s lots of things that happen, our data collection can happen, independent of the weather. Questions like ‘how does the pipeline actually operate?,’ ‘what does it take to shut it down if something does happen?;’ all those answers we can get independent of the weather. And then as we come into springtime, there will be site visits, there will be a draft report and an opportunity for the public to participate in the process. The public will be given the opportunity to comment just like the last alternatives analysis which received more than 25 thousand comments. They’re in the process of responding to those. So that will be a task also.

GLB: What is the ultimate goal of this report?

Dr. Meadows: The Pipeline Safety Advisory Board is composed of experts. The ultimate goal is to evaluate and put in dollar value each particular threat that would occur if there was a worst-case scenario. There is a giant economic analysis that goes along with this that sums it all up. The ultimate goal is to provide the state with a realistic number of what it would cost the state if this would happen: what is the environmental damage, what is the human health damage, what is every single damage we can think of with input from the public; everything that they can think of that needs to be included, and get an economic analysis: this is what the cost would be. And then it would be my guess that as part of the 1953 lease, Enbridge would put that quantity of money in some sort of Escrow account so it is there and available in the event a worst-case scenario should happen.

GLB: SO: what is the clear definition of a worst-case scenario of an oil spill from Line 5?

Dr. Meadows: We don’t know that yet. I’ve asked for assistance from the Pipeline Safety Advisory Board, at the last meeting, to have them participate in the definition of that scenario and, again, because they are experts and they represent 19 other points of view, I think that would be a very helpful situation. Because whatever anyone decides, someone is going to think that’s not going to be enough. There has to be some sort of a bound. Throughout this process, this is truly going to be a team effort.

1 Comment

-

I live in Southern Ontario. This is very exciting.