The similarities between the early years of President Ronald Reagan’s Environmental Protection Agency and that of the President Donald Trump’s first months are striking.

Both presidents positioned environmental regulations as the enemy, alleging that they overreach and stifle economic growth. Shortly after gaining office, they moved to dramatically slash the EPA’s budget and staff and they de-emphasized enforcement of regulations in favor of a pro-business culture.

Richard M. Nixon signing a bill, courtesy of Office of the President

They are the only presidents to take that approach to the agency since it was founded by President Richard Nixon in 1970. And Reagan retreated after two years under congressional pressure amidst an EPA scandal.

That’s the assessment of the Environmental Data & Governance Initiative, a nonprofit that supports evidence-based policy making. The initiative is currently tracking the Trump administration EPA.

EDGI reports that in Reagan’s first years the EPA budget was cut by 21 per cent from $4.7 billion to $3.7 billion. The staff was slashed by 26 per cent from over 13,000 to 11,000.

Trump’s first budget proposed a chop from $8.1 billion to $5.7 billion and a staff cut of over 3,000.

The Reagan cuts were implemented, whereas Trump’s are still a work in progress and won’t be approved at the level he desires, at least not in his first year in office.

To find out what it was like during those early Reagan years at EPA Great Lakes Now talked with long-time Great Lakes executive David Ullrich.

Ullrich started as an enforcement attorney at the EPA in 1973 and finished his career in 2003 as Deputy Regional Administrator in the Region 5 office in Chicago that houses Great Lakes programs. He then led the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative until retiring in July.

“Devastating effect”

The first two years of the Reagan EPA under his administrator Anne Gorsuch, “had a devastating effect on EPA,” Ullrich said. “It was clear that their desire was to undo everything that had been done in the 1970’s whether done by Republicans or Democrats.”

Ullrich says budgets and staffing levels are important but emphasizes that policy signals are equally important and policy direction on enforcement was clear.

“Messages were sent by Gorsuch that the EPA had been too stringent in enforcing laws” and it was time to back off, Ullrich said.

It was clear that enforcement was not a priority and the unofficial word was that enforcement actions could be viewed as a black mark on one’s record, according to Ullrich.

William Ruckelshaus swearing in as the first Administrator of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, courtesy of Office of the President

This was strange territory for Ullrich who was used to the mission-driven EPA established by the agency’s first administrator, William Ruckelshaus, who was appointed by President Richard Nixon.

“What made Ruckelshaus so important was that he took a new agency with new laws, like the Clean Water Act, and put it on the map in a time of political and social turmoil,” Ullrich said referring to the Watergate scandal that ended in Nixon’s resignation.

“He made it clear that environmental laws needed to be taken seriously” and went after the worst corporate polluters in court, Ullrich said.

During those early Reagan years, Ullrich faced a decision he wasn’t expecting so soon in his career.

He said “morale was in the tank” and that he came close to leaving the agency but decided to stay. “They were trying to drive people like me out of the agency and I wasn’t going to give them the satisfaction of leaving voluntarily.”

It appears Ullrich made the right choice. A year into Reagan’s first-term, the slash and burn tactics that eschewed enforcement of regulations started to collapse.

in 1982 the House of Representatives began to receive reports of failure by the Gorsuch EPA to prosecute known polluters and of corruption in the Superfund program that was established to clean up the worst toxic sites.

Democrats were in the majority and along with moderate Republicans with pro-environment leanings, they began to investigate.

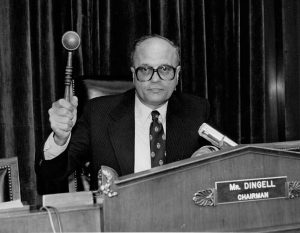

U.S. Rep. John Dingell with gavel as chairman of an unspecified committee, courtesy of U.S. Congress

Michigan’s John Dingell led a committee that requested documents concerning the Superfund program and Gorsuch refused to turn them over. Dingell used his congressional subpoena power to force Gorsuch’s hand but she still refused and was charged with contempt of Congress.

Veteran Great Lakes policy expert Dave Dempsey watched this unfold early in his career and he told Great Lakes Now that in her actions toward Dingell, Gorsuch was defying “one of the finest conservationists ever to serve in Congress.”

Dempsey is currently advising Flow, a Traverse City nonprofit legal and policy center focused on the public trust in Great Lakes resources.

Gorsuch’s EPA tenure came to an end when she resigned in March of 1983. That ended Reagan’s “frontal attack on the EPA,” according to the EDGI report.

Reagan was done trying to disrupt what had been an EPA that functioned well under both Democratic and Republican presidents.

The pragmatic side of Reagan brought Ruckelshaus back to restore credibility and integrity to the agency. Ullrich called Ruckelshaus’ work after returning to the EPA “phenomenal.”

With stability re-established, the EPA continued on an even keel through the balance of Reagan’s term and the presidencies of George H.W. Bush, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush and Barack Obama.

Though late in the Clinton administration staff levels and funding began a slow but steady decline that continued through the Obama years, according to the EDGI report. Staffing dropped from a peak of 18,000 in 1996 to just over 15,000 in 2016.

The initial decline was attributed to increased pressure on the agency by congressional Republicans initiated in Newt Gingrich’s years as leader of the House.

Ullrich told Great Lakes Now that at the regional level he had a lot of autonomy but he was aware of the congressional pressure on EPA’s headquarters in Washington.

President Barack Obama writes at his desk, courtesy of Office of the President

Further evidence of that pressure came after the 2010 mid-term elections when Republicans took back control of the House. President Obama cut funding for his newly-minted Great Lakes restoration program from $475 million to $300 million where it has been since.

Trump’s first budget proposal shocked the region when he zeroed-out funding for the Great Lakes saying the money was needed to fund the wall between the U.S. and Mexico.

His budget director, Mick Mulvaney – like Reagan’s budget director, David Stockman – promoted the cut saying the Great Lakes had received substantial federal money and it was now time for the states to assume responsibility for their health.

Congressional appropriators – the committee that funds the government – were having none of that and in a bi-partisan move restored the full $300 million to the budget though, it’s not final yet.

To Ullrich’s point on regulation and enforcement, the House took action to facilitate roll back of the Clean Water Rule designed to prevent pollution.

And even though the Obama’s EPA championed the Great Lakes and the Clean Water rule under Administrator Gina McCarthy, it could be lax in its oversight of the states.

It failed to take action on Lake Erie’s algae problems after the Toledo water crisis instead deferring to Ohio.

And EPA was late in dealing with Flint’s lead problems which contributed to the resignation of Regional Administrator Susan Hedman.

The Detroit News reported that she knew about Flint’s lead issue for month’s before it was disclosed publicly but said nothing, instead referring the issue to attorneys for an opinion on EPA’s authority to act.

McCarthy defended EPA and Hedman’s role on Flint in testimony before congressional investigators.

Which way now?

President Donald Trump at a Cabinet meeting, courtesy of Office of the President

President Trump’s first year EPA budget will likely be cut by $528 million, a far cry from the $2 billion he requested. Staff reductions are in progress by incentivized early retirement packages, not slash and burn reductions.

Rumblings from disgruntled activist staff are that they fear enforcement will diminish. And the Washington Post has reported on favorable EPA decisions toward corporations after Administrator Scott Pruitt met with their executives.

A Congress controlled by Republicans has sent a message that funding for the environment is important. That same message hasn’t been sent on regulation and enforcement and it’s unlikely that Congress will buck the pro-business president on that issue.

If Trump has been anything in his first nine months, he has been unprincipled and erratic. And Pruitt recently praised the Great Lakes restoration program that he originally told Congress should be de-funded.

David Ullrich fears that they have a “longer term plan that is a reflection of their anti-environment policies and that the priority is to protect big business.”

Ullrich believes “the fundamental values of the American people are that they want a clean environment and strong EPA.”

Will Trump and Pruitt follow the Reagan model and return to even keel management of EPA that has been the hallmark of Republican and Democratic administrations?

As President Trump is fond of saying on other issues, “time will tell.”