Mayors seek collaborative process improvements

Waukesha, Wisconsin cleared the last hurdle yesterday that could have prevented it from drawing from Lake Michigan for its drinking water needs.

In an action with long term implications, a regional group of Great Lakes mayors decided not to pursue a lawsuit to overturn or reopen the decision by Great Lakes governors who had granted Waukesha’s request over a year ago.

In exchange for not pursuing a legal remedy, representatives for the governors, known as the Compact Council, agreed to establish and work with an advisory committee to update procedures on how to handle future water diversion requests.

The mayors will be on the committee but it will not be exclusive to them.

It will be open to other stakeholders including citizens and Tribal and First Nation governments, according to Peter Johnson. Johnson is a director of the Conference of Great Lakes Governors and Premiers, the secretariat of the Great Lakes Compact that governs water diversions.

President and CEO of the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative

Part of the mayors’ objection to the original decision was that the “process was flawed,” John Dickert told Great Lakes Now in a phone interview following the announcement.

Dickert is President and CEO of the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative, the U.S. and Canadian group of mayors who objected to the decision.

Specifically, Dickert said the original review process did not have a sufficient number of public hearings.

But Dickert said the mayors “concluded that they should work toward a more inclusive process” and that they “will meet with representatives of the governors to develop procedures and guidelines” for future requests.

The eight-page agreement written in legalese says the mayors “concluded that its and the public’s interest can best be satisfied” by participating in a review to update procedures “rather than pursuit of an appeal” of the governor’s decision.

In a statement, Waukesha Mayor Shawn Reilly said it was appropriate to “recognize all the tremendous work by the Great Lakes governors and premiers in reviewing our application.”

Shawn Reilly, Mayor of Waukesha, Wisconsin, courtesy of the City of Waukesha

Reilly said Waukesha is “committed to the health of the Great Lakes and its tributaries and to being good stewards of this vital asset.” He expects to take the first water from Lake Michigan in 2023.

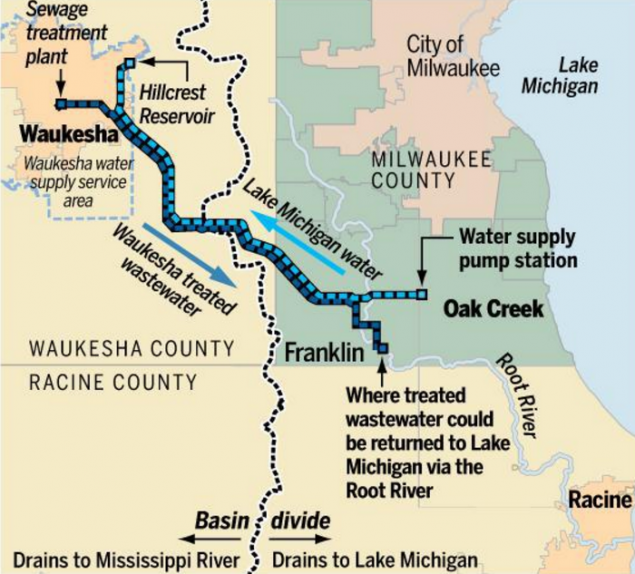

Waukesha has been under a federal mandate to find a new source of drinking water as its wells are contaminated with radium. It determined that Lake Michigan was the most viable source but it isn’t automatically entitled to Great Lakes water as it is not in the Great Lakes basin. But under an exception provision of the Great Lakes Compact, Waukesha sought and eventually received approval following a protracted process.

There was significant objection to granting Waukesha’s request from environmental groups, the mayors and others. But most groups signed off on the diversion when Waukesha made concessions on how much water it would take.

That left the mayors in the difficult position of not having allies to bolster a legal challenge.

Michigan played a key role throughout the Waukesha decision-making process. Grant Trigger, representing Michigan’s Office of the Great Lakes, served on the Compact Council where he led the other states and Canadian provinces through a detailed technical review of Waukesha’s request.

Grant Trigger, courtesy of Gary Wilson

On the settlement agreement Trigger said “everyone who cares about the Great Lakes can now look forward and not look back.”

With the Waukesha decision final, Trigger compared the process to the political situation in Washington under President Trump where partisan divides and a lack of collaboration are prevalent.

In the end, the Waukesha decision was “a model of a collaborative, non-partisan process which included Canada,” Trigger told Great Lakes Now.

Work to establish the advisory committee begins in September with the goal of publishing rules and guidance for future diversion requests in October 2018.