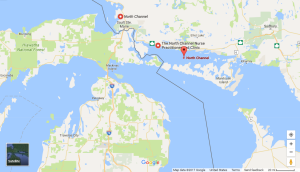

I’ve heard tales about the hidden coves and pristine shorelines of Lake Huron’s North Channel for most of my adult life and had always longed to see it. Earlier this year, friends invited my husband and me to join them on their Beneteau 49 sailboat named “Adventure” for a five-day trip to explore the area between Manitoulin Island and Ontario’s mainland.

We answered an enthusiastic “YES!” but explained to them that we might not be the most experienced sailors. They understood that we would be quite useless, but kept their invitation open to us anyway.

We decided to set sail the first week in August.

We drove across the Mackinac Bridge into Ontario, through small villages along the North Coast of Lake Huron. Many of the towns we passed through were First Nation Communities. Evidence of Ojibwe history appeared throughout our trip.

We met Paul and Cheryl the evening of August 3rd in Little Current, Ontario, a tiny town nestled in a cove on the world’s largest freshwater island of Manitoulin. The name “Manitoulin” means “spirit island” in Ojibwe.

Little Current is famous for its swing bridge that opens every hour to let tall boats through the narrow channel between Manitoulin and Goat Island.

The town was packed with people celebrating the 50th anniversary of Haweater’s Weekend. “Haweaters” is a nickname given to natives of Manitoulin who eat the hawberries growing on the island. Early settlers in this part of the Great Lakes reportedly got their vitamin C to prevent scurvy by eating these tiny red berries from hawthorn trees. But no hawberries were available the weekend we arrived – they ripen in late fall.

We ate delicious freshly caught whitefish for dinner at a restaurant in Little Current, just around the corner from the marina and tasted Manitoulin Island’s famous craft beer called “Split Rail,” named after the fences that divide farmland on the island.

We retired early to the cozy aft berth of the Adventure.

The next morning at 9 a.m., we motored past the swing bridge and watched in awe as the 104-year old bridge – one of the only swing bridges in Canada – pivoted perpendicular to the road to open the channel at 9 am. We sailed about 6 miles on the open water, gazing out at the beautiful pine forests and uncluttered shorelines, until we saw a group of smaller islands and the entrance to a channel called Baie Fine.

The narrow waterway is considered the only fjord in North America and is one of the largest freshwater fjords in the world.

The view is breathtaking: high white quartzite mountains that are part of the La Cloche Mountain Range, deep blue water, windswept pine trees, and tiny islands.

But about a mile up Baie Fine, we saw the dangers of the North Channel up close: a 45-foot cruiser resting precariously on a group of rocks. Rescue boats circled the scene of the accident. The boat had struck the outcroppings just two hours before we entered the channel; the owner’s summer vacation bashed and broken in a matter of seconds.

We watched from the bow of The Adventure with a new kind of vigilance from that point forward.

What struck me most as we motored up Baie Fine: hardly any sign of civilization except for a few boats and a resort along the entire 9-mile length of the fjord. A rustic cabin which had no road access appeared on one of the many small islands from time to time. Only a few cabins had conventional electricity.

We continued east down the channel until we saw cliffs that looked like Western U.S. mountains, then headed south into a still and lovely cove called The Pool. Only two other boats had anchored there, and our captain Paul chose a prime spot in the center for us to settle for two nights. We heard the eerie cries of loons shortly after we arrived.

At a corner of the cove near the entrance to the Pool is a log cabin perched on a large rounded rock with several canoes and rowboats, where the Group of Seven landscape painters (also known as the Algonquin School) often stayed. In the early 1900’s, they created a specific Canadian school of painting that helped establish a sense of national identity based on the sublime landscape of Northern Canada.

When we knew the anchors were secure (quite a task for Paul, who set two anchors in the reedy, grassy bottom of the Pool) we took the dinghy to a weathered dock in a corner of the cove, beached the dinghy, and hiked up a trail lined with ripe blueberries for about a half mile. At the top of the trail, a stunning body of water appeared: Topaz Lake, in Killarney Provincial Park.

The lake, surrounded by huge white quartzite cliffs, is known for its brilliant deep blue color but on the day we visited, it was more of a dark greenish hue than glistening Topaz.

My husband and Paul dove into the chilly water. Cheryl and I remained on the shore, watching swimmers jump off 30-foot rocks.

We trekked back to the dinghy as we ate blueberries along the way.

As we took the dinghy back to the boat, we encountered several loons. We thrilled at the close-up view of the white and black cross-hatchings on their backs, the white rings on their necks, and a flash or two of the loon’s stunning red eyes.

Back at the boat, I summoned my courage, donned my bathing suit, and dove in to the Pool. I was surprised: it was as warm as an Inland Michigan lake in summer. The scent of the water was fresh and clean but pungent, and unlike anything I had smelled before.

Paul and Cheryl made a lovely dinner on a grill attached to the back off the boat. We slept well in the quiet cove – no boat wakes, no sounds of partying boaters!

Next morning: Cheryl made mouth-watering pancakes with the blueberries she and Paul had picked along the shore, served with Canadian maple bacon.

It rained off and on, but we explored the cove and hiked along the edge of the Pool, swam some more and read. Seven loons came to visit us off the bow of the boat, and stayed for some time to look for food in the reeds and grasses near the Adventure.

The following day, it was sunny, warm and still. We left the cove early to get to our destination. Another pair of loons came to the entrance of the Pool as if to see us off on our journey. It was difficult to leave that serene spot, but we knew another adventure was ahead: the trip to Killarney at the north end of Georgian Bay.

As we motored back down the Baie Fine fjord, we noticed the cruiser that had run aground on the rocks had been hauled away.

It was a perfect day to head down into Frazer Bay and into the Landsdowne Channel to get to Killarney in time for a hike and dinner. Once again, more vistas of beautiful shorelines and undeveloped forests. The only interruption: a quarry mine no longer in operation that carved up the landscape along the shore not far from Killarney.

A lighthouse appeared – this one, an unusual pink color – and then a small channel came into view. We saw a tiny town that seemed to be a fishing village from another century and an historic stone church.

Killarney, named after the Irish town by the same name, is settled on either side of a channel where boats pull in to port for short and long summer vacations. Free fast-moving water taxis (beat-up float boats commandeered by fun-loving teenagers) transport visitors across the channel to restaurants and marinas.

Killarney is one of the oldest villages in Northern Ontario, dating back to the early 1600’s when Europeans opened up the area for French fur traders and to develop the fishing industry.

For many years, the village was known as “Shebahonaning”, an Ojibwe name meaning “canoe passage”.

Now, it’s mainly about restaurants, homemade crafts, and smoked fish you can still buy off the docks.

Though we took a short walk up the hill to get a view of the quaint town, the long hike disappeared from our plans when we discovered a new place called “Big Willy’s Bait Shop” that sold freshly caught oysters brought in from Toronto had just opened up along the water.

We enjoyed another whitefish dinner that night at a favorite boaters’ hang out called The Sportsman’s Inn.

That evening, three river otters swirled around the boat and made squeaking noises at our slip in the harbor. The shiny pelt which helps maintain the otters’ temperature is one of the reasons Killarney became a center of the French fur trade.

The following morning, we took a leisurely trip back out to the Landsdowne Channel to return to Little Current. We didn’t make the hourly swing bridge window we had hoped for, so we swam around the boat as we waited near the Strawberry Island LIghthouse. The temperature of the water between Goat Island and Manitoulin Island was surprisingly comfortable.

Once in port again at Little Current, we headed into town for our final whitefish dinner at the Anchor Inn. But the adventure wasn’t over. The night ended with a huge full moon that glowed orange-red on the horizon by the swing bridge.

The next morning, Paul and Cheryl left early to catch the swing bridge opening so they could sail home to Detroit along the coast of Lake Huron. We waved goodbye as we watched the boat disappear into the sunrise.

This trip to the North Channel showed me some of the secret places the Great Lakes hold: glacier lakes, fjords similar to waterways in Scandinavia, windswept pines on sandy beaches, rocky cliffs, and hidden coves.

And there is so much more to discover.

3 Comments

-

Thank you for your lovely words. I have sailed the North Channel many times — first with Dad, and then with my husband. It was always a magical experience which you have captured so perfectly. This morning you allowed me to sail those waters once again, and dream of a time when we might return.

-

I hope I can boat it one day!

The Mackinac Bridge is in Michigan, joining the Upper and Lower Peninsula’s. Did you mean the International Bridge to Ontario?

-

I have sailed in the North Channel and lived aboard a sailboat twice for a year at a time. The North Channel & Maine are my most favorite waters to sail. Soon will be publishing a book about our sailing adventures. ‘Down to the Sea Again”” Jim & Angie George Bookbaby is the publisher.