By Elizabeth Miller from Great Lakes Today

There’s more than just fish and sand in the Great Lakes. According to the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum in Michigan, there are over 6,000 shipwrecks in the lakes – and an estimated 30,000 lives lost.

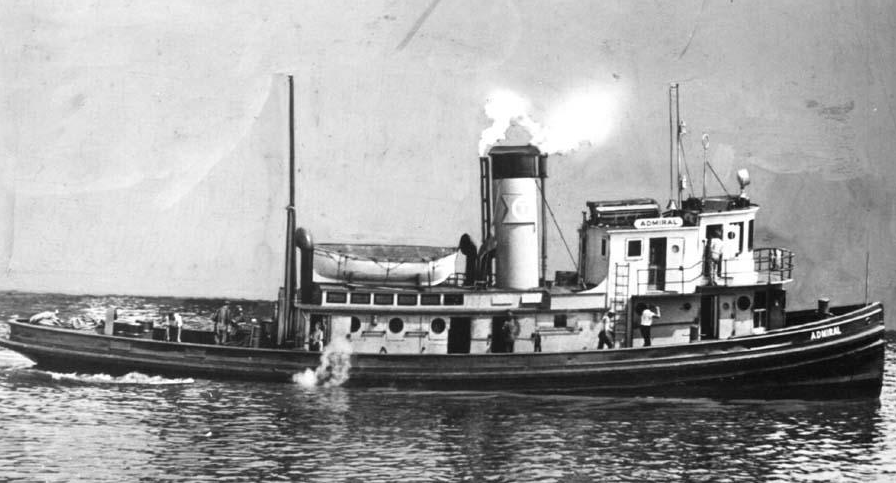

About 13 miles from Cleveland, the tug boat Admiral sits on the bottom of Lake Erie. It sank in a storm in December of 1942, and its entire crew, 14 men, died. The 18 men on the Cleveco , the oil barge it was towing also died.

Carrie Sowden, archeological director for the National Museum of the Great Lakes, is taking a group of volunteer divers out to the Admiral to help with a site survey.

“What we’re trying to do is take a snapshot of what’s down there at the moment, to get an understanding of how the boat lies, what remains of the vessels are left, what has fallen apart, what hasn’t. Any clues to what may or may not have happened the night that it sank,” she says.

Sowden trained the 14 divers through a workshop with MAST – the Maritime Archaeological Survey Team. The group includes people who have dived all over the world.

This is Amanda Holdeman’s first time diving in a Great Lake. The Dayton, Ohio, resident says the experience is very different from diving on a remote coral reef.

“When you go to the Great Lakes and see modern shipwrecks, you get that sense of – there were people here, there were people traveling here,” she says.

Groups like MAST aim to bring these shipwrecks to life. They search for answers to the mysteries of the thousands of wrecks littering the region’s waters.

Holdeman says she enjoys the “detective work” that goes into diving for history’s sake. “You start off with one little piece of information that you can physically see, and then you go to records and you just build stories off of that.

“You’re looking at the bigger picture and the smaller picture, and you’re going back and forth and putting it all together.”

The divers board the Holiday early on a Sunday morning. On the hour-long ride to the wreck, they chat and drink coffee. And as the boat reaches its destination, a few divers start to get ready.

Holdeman and her diving partner are up first. They’re covered in full body suits with goggles, fins, tanks, and dive computers on their arms.

Each pair also carries tools to measure and record the boat’s description and dimensions for the survey. Sowden gives every diver an assignment.

“To do the measuring we have these fiberglass tapes,” Sowden explains. “You use coated plastic and Mylar to write underwater with a pencil, take all your notes on it.”

The water is about 54 degrees, which can make writing difficult for cold, glove-covered hands. But the fresh, cold water in the Great Lakes preserves metal ships like the Admiral much better than saltwater.

That gives divers like Patrick Enlow of Dublin, Ohio, a good look at the tug: “You see an old wreck that’s covered in mud and muck, but you also see some of the damage done to the ship.

“The area on the starboard side that we were measuring, you’ve got a porthole in the door and this giant gaping hole – which is not normal.”

Several in the group traveled to Cleveland for the weekend’s survey – including Robert Lukofsky of Livonia, Mich.

He and diving partner Todd Felton of Columbus, Ohio, run into a problem trying to survey the tug’s smokestack.

“We expected one end to be buried and the other end to be exposed,” Felton says. “We found that both ends were mostly buried!”

After its discovery in the 70s, divers took items from the Admiral , but today, an Ohio law prohibits taking artifacts from shipwrecks.

Lukofsky says it’s important to preserve the past. “What you leave there, everyone can see. What you take, only you have.”

Sowden hopes to publish her report on the Admiral next year.

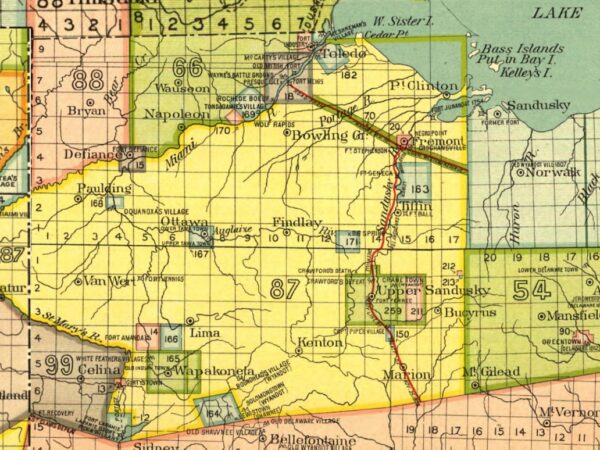

And if you can’t dive, you can still see some artifacts from the Admiral – they’re on display at the National Museum of the Great Lakes in Toledo.