A spike of 78 percent.

That’s how much drownings increased last year in the Great Lakes.

Some 98 people – including 46 in Lake Michigan and nine in Lake Superior – lost their lives in the Great Lakes in 2016.

In 2015, 55 people died: 25 in Lake Michigan; two in Lake Superior.

The Great Lakes Surf Rescue Project says there have been 20 drownings in the Great Lakes already this year, with 12 of the drowning deaths were in Lake Michigan.

Jamie Racklyeft , Executive Director of the Great Lakes Water Safety Consortium, courtesy of greatlakeswatersafety.org

Executive Director of the Great Lakes Water Safety Consortium Jamie Racklyeft says, “Every one of these drownings is avoidable.”

And he says many of them are caused by rip currents.

Racklyeft is a guy who knows a lot about the power of the waters in the Great Lakes. He almost lost his life in deadly rip currents in 2012.

Racklyeft headed to the Sleeping Bear Dunes near Traverse City for a much-needed vacation that summer. He decided to swim in the waters off Leland.

“I’ve dedicated my life to making sure this doesn’t happen to anyone else”

He was waist-deep in water, and then Racklyeft says, “Pretty soon I noticed I was up to my chest. As I’m trying to walk back towards shore, I realize I’m moonwalking. I’m actually working my way backwards into the lake as I’m walking toward shore.”

He says he knew right away what was happening. “It was one of those rip currents. I learned about this on ‘Bay Watch’ “, he joked, “the most educational program of all time!”

He says he even remembered that he wasn’t supposed to fight the current. He flipped over on his back so he’d be less likely to inhale water, and he started swimming to the side, instead of directly towards shore. But, says Racklyeft, “The waves were so big and strong and relentless, I kept getting knocked down. “

He says darkness began to surround him, and he thought, “No one can save me. No one can hear me. I realized, ‘This is it, this is how I’m gonna die.’ To go from a beautiful, incredible day.. to this. But this is it. This is all I’ve got.”

He says, “Everything got quiet. Then I felt like I was being carried. I heard muffled voices. Pretty soon, I felt I was being set down on warm sand. People were asking me if I was OK. I asked people if I was dead. I was arguing with them!” Suddenly, he says he realized he had been saved.

Racklyeft discovered that “two brave strangers had commandeered a kayak and got to me at the last possible second.”

But it turns out he was the lucky one.

He found out a few days later that 45 minutes after he was rescued, a 15-year old boy was caught in the same rip current, and no one saved him. He drowned.

Racklyeft says his life changed in that moment. “Since then, I’ve dedicated my life to making sure this doesn’t happen to anyone else.”

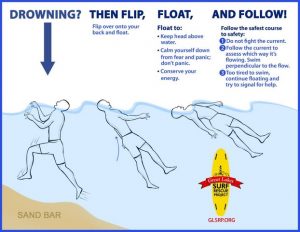

Flip, Float and Follow

Since that day, Racklyeft has been bringing experts together, meeting families of victims, and trying to understand their heartbreak and grief.

He says one of the biggest problems is that people don’t realize there are rip currents on the Great Lakes. “We hear about them in the oceans. We didn’t really know until recently that they exist on the Great Lakes.”

550 people have drowned in the Great Lakes since 2010. He believes that climate change plays a part: warmer waters and warmer weather are beckoning people to the lakes and beaches in greater numbers, and there are more dangerous currents caused by weather changes, too.

Racklyeft’s organization, The Great Lakes Water Consortium, meets on a regular basis to share techniques and technology to prevent drowning deaths. The most recent conference was held in Cheboygan, Wisconsin.

Racklyeft says he “wants people to know how to avoid drowning, how to escape drowning, and how to save others from drowning.” A few points he wants to drive home for people to remember so they won’t get in trouble in the water:

- KNOW BEFORE YOU GO. (Check with the weather service for warnings about rip currents and hazardous conditions.)

- WHEN IN DOUBT, DON’T GO OUT.

- STAY DRY WHEN WAVES ARE HIGH.

- FLIP, FLOAT, and FOLLOW.

Racklyeft says here’s the routine: if you DO begin getting caught in a current, remember to flip over on your back to save energy and don’t panic. Float so you won’t get worn out. And follow the path of least resistance to shore.

And to safely save others, don’t run out in to the waves to rescue someone without some sort of floatation device: a football, a kayak, a boogie board, or even a piece of drift wood.

Meet Emily, the drone that could save your life

It is possible in the future, says Racklyeft, that drones could wind up saving lives on the Great Lakes, too.

Demonstrations of two drones were held at the most recent conference. One of them is called E.M.I.L.Y.

EMILY the drone, courtesy of greatlakeswatersafety.org

The yellow buoy – about 4 feet long – can travel more than 20 miles per hour to speed through rip currents to take a life vest and helmet out to victims, or simply give them something to hang on to until help arrives. The problem: they cost more than $10,000.

Racklyeft wants to find a way for Great Lakes communities along shorelines to afford these. He says the lives of rescuers would be saved by these devices, too, because they could use the drone to help, instead of putting their own lives in danger in rip currents.

Racklyeft says summer is the time to warn people about techniques to prevent drownings. However, he says, “drownings happen year round. The more we get the word out, the better.”

For more information on Racklyeft’s organization, go to Greatlakeswatersafety.org.

Other places to check out for safety tips and facts about drownings on the Great Lakes :